How not to play the piano, featuring my hand. How not to play the piano, featuring my hand. How often do you practise your instrument? How often do you play it? What do these two terms mean to you? How are they different and how do they overlap? Practice is always a hot topic in music teaching - how much should students practise and how should they practise? There's more talk about practice strategies these days than there is about lengths of time, but the "how long should I practise for?" question still pops up repeatedly. Music teachers still vent their frustrations over students who "don't do enough practice". I find that adult students in particular tend to 'confess' to a lack of practice - many, many lessons begin with "I haven't done as much as I'd like/ I should have". Sometimes that means they haven't had the time/ energy/ motivation and they've hardly picked up their instrument. But sometimes, it turns out that it means "I haven't worked on the pieces we worked on in my last lesson, and I haven't done those exercises that we agreed would be beneficial to improve my high notes, but I have played my instrument at wind band, and met up with some friends to do quartets, and played along at a folk session in the pub". Yet, they feel like a 'bad pupil' because they haven't done the assigned tasks. The interplay of play and practice isn't always easy to unpick - I like a sports analogy when it comes to learning music, but is it really like football, where you train (practise) then go out and play a game (perform) or is it more like yoga where the doing (playing) is also the practising? Is it somewhere in-between or a mixture of the two? With the student who's doing lots of playing, I always think (and say) that that's brilliant, it's what playing an instrument is about! Playing is both practice in itself, and putting practice into action. You learn so much from playing with other people, you get pushed by having to 'keep up', you pick up or improve skills in context. So why do we do this other thing, this practising which is generally less fun and less 'musical'? The simple answer to that is that practice builds the skills that make playing more enjoyable. If you join an ensemble but find it difficult to play at the speed that everyone else is galloping along at, you might feel frustrated. Then practising exercises on your own that will help increase your finger speed will hopefully lead to a more comfortable experience in the group, feeling like you're part of making music rather than struggling to keep up. If you feel self-conscious because your high notes are squeaky or out-of-tune, then working on those in isolation boosts your confidence when you next share them with other people. We practice scale patterns because it means that when we're presented with a new piece of music, some magic* thing occurs in our brains which means we see that string of notes and our fingers know exactly what to do to produce them (*not actually magic at all, but it can seem like it if you've never reached that point yourself, and even if you have, sometimes you still step back and think "woah, how DOES that happen?"). I will admit to some, err, debates with students over practice, but it tends to be when they've set themselves a goal, such as an exam, but aren't doing the things they need to do to reach that goal. Even then, often the problem is not so much not practising their scales or whatever, but actually just not playing the instrument very often. And perhaps that is in part because they feel that if they take it out to play then what they should be doing is practising, and practising is hard and not always fun. Whereas the difficult practising bits would actually be made easier by the familiarity with your instrument that comes from playing it regularly. I've experienced this myself with the piano. I neither play nor practise the piano very often. Sometimes I'll sit down to play something on it, but because I'm nowhere near as familiar with it as I am with the flute, I get frustrated by not being able to do things so easily. I 'need' to play the piano maybe a couple of times a year, to accompany early grade students in exams, and these accompaniments which I think I should be able to play quite easily sometimes take a fair bit of practice. However, I KNOW I actually enjoy playing the piano when I feel more competent at it. I don't love it in the same way as I do playing the flute - it doesn't feel the same to me as a way of expressing things through music - but it is a useful skill in my line of work and, well, I think I'm intrigued as to what playing the piano better would actually feel like! I really enjoy accompanying, but I know that my skill level limits how much of this I can do. So, I've set myself a challenge, to do some regular piano practice and playing. I've chosen three pieces, initially, that I want to work on 'properly'. I've got a list of scales and arpeggios from a particular grade exam to try to master, because it seemed like a good point to aim at, to start with. I've got a big pile of books to pick and choose things to try out, so I'll also be playing as well as focussed practising. I'm going to give it a try over the summer, while other work is quieter, and see what happens when I practise what I preach! I'll let you know how I get on.

0 Comments

A reporter once asked the celebrated orchestra conductor Leonard Bernstein what was the most difficult instrument to play. "Second fiddle! I can always get plenty of first violinists, but to find one who plays second violin with as much enthusiasm, or second French horn, or second flute, now that's a problem. And yet if no one plays second, we have no harmony.” It's supposed to be the pinnacle of ensemble playing, being on the 'first' part. It means you're the best, you can play all the hard stuff, you can do the twiddly bits. It's just one step down from being a soloist. It's fascinating watching the jostling for position - both physically and metaphorically - that can happen in some groups. So-and-so should play first because they've been here the longest. Whatshername should do it because she's 'better'. Ask a big group of musicians to allocate themselves to parts and some will rush to either end - they want to play first because they're 'good enough', or they want to play fourth or fifth because they're 'not good enough'. They want to show off or they want to hide. They'll insist on playing the top part or they'll step back and offer it to someone who they think is better than them - there can be a game of "no, no, after you"... "no, no, I insist". This ranking of musicianship is ingrained in us from the early stages of playing - 'first' is something to aim for, it's where the better players end up. And it's true that first parts tend to be more technically challenging and mostly, in a higher register, which is something that flute players, at least, learn as we get more advanced. But that doesn't mean that playing second (or other parts in different ensembles, such as a flute choir) is easy or any less valuable. You might not get the high twiddly bits, but you might have a vital harmony part. Can you blast out those lower notes so they blend with the higher ones elsewhere rather than being drowned out by them? Can you maintain a repeated pattern on the same couple of notes for ages without it losing energy? Can you handle playing on the off-beats for ages? Can you concentrate to count for lots of bars rest?! Can you match your sound to that of the person playing first? Someone once described the role of orchestral flutes to me as the first providing the 'colour' and the second having to adapt into that first players sound - that's quite a skill. Sometimes the second or third part will be doing something completely different to the first, and having to blend with the violins or the French horns. As individual instrumentalists, our education doesn't always prepare us for this - flute players, for example, mostly learn solo repertoire. We're used to playing the tune (I've had transfer students who could only play the top line of duets because they'd never played the second part - they found it such a challenge visually to follow the lower line!). So when we join an ensemble, we might opt for what seems like the 'easier' part, but then discover that it isn't that at all. We're not accustomed to playing harmony parts, to making so much use of our low notes, to playing parts with so many gaps in them. Equally, ensemble directors might order the parts with the most experienced players on first and least experienced on 'lower' parts, and find the balance really not working. I wish we could get away from this idea of first as better. One of my very accomplished flute colleagues likes to sit in different places at our ensemble rehearsals, and noted that some less advanced players asked why she was "lowering herself" to play third or fourth flute. But it's enjoyable, good for your playing, and great for exercising different skills to mix it up. In the orchestra I play with, we have three regular flautists, and we rotate around parts, depending on who would prefer to play what and playing to our strengths. For our next season, we're playing first for one concert each, and second for one half of each of the other concerts (with the occasional piece that needs all three). We figured it out through an online chat whilst one of our number was sunning herself on holiday, and I was on my sofa. We put forward our requests to play certain parts because of musical preferences, because we wanted to be in or out of our comfort zone, and so we could have a quieter time when other parts of our lives were hectic. It works - nobody feels left out or under pressure. It keeps us on our toes and makes us better players because we all get a turn at the twiddly bits, the harmony bits, the counting, the matching our sound to other people's. So, I guess this is an appeal to players, not to get hung up on the numbers. The composer wrote two parts or seven parts because they wanted them all, so they're all important. Try them all. Feel how glorious it is to play a bassline, to harmonise under the melody. Twiddle away on top or embrace those syncopated rhythms in the middle. And to teachers, too - get your students playing duets with you, and group pieces with each other, right from the start. Help them to be a flexible player who can happily get stuck in with any part of an ensemble and do a great job of it. A few links:

This article by flautist Rachel Taylor Geier has a great summary of the skills needed to play second flute. An excellent blog post by David Barton Music about the role of duets in lessons. "Who's on first?" - nothing to do with music but I was introduced to this comedy sketch last year, it inspired the title of this post, and the play on words makes me laugh so much! Why do people play musical instruments? Why do they have music lessons? There are all sorts of reasons. To quote one of my younger students "I just like the sound!" - that's usually a big factor. Quite often, especially with adult students, there's a desire to to learn so they can play in a group. Even if the initial decision to learn is because you 'like the sound', people often develop ambitions to be able to join an ensemble or to play together with friends.

It sounds like a good plan, to get to the stage where you can play with other people, but I think there's a lot to unpick here. For me, playing with other people is a huge part of what playing music is 'about' - the communication, the connection, the teamwork, the blending of sounds - and I can probably be a bit evangelical about it. But it isn't a compulsory aspect of learning an instrument, and it is absolutely fine if what you want to do is play on your own, in your own house, because you like the experience of making a nice sound, but feel no particular desire to do that anywhere else or with anyone else. Music in this way can be very therapeutic - sometimes it's an escape from the stresses of life. Sometimes I shut myself in my spare room and just play whatever I feel like, and it makes me feel better. I'm also somewhat bothered by the idea that you have to reach a certain level of competency to play with other people - you have to be 'good enough'. Of course, if an established ensemble has a minimum standard, then obviously you have to meet that to join. In some cases, this can be a good motivator to practice and improve your playing. Sometimes you need the 'piece of paper' to show you're the appropriate standard, and I've had students set themselves goals of passing a particular exam so that they can join the next level up of school orchestra, or their nearest amateur wind band. However, I strongly believe that as long as you can make some sounds, you're 'good enough' to play with others in some way, if that's what you want to do. When I run student workshops, everyone is invited, no matter how long they've been playing for - and when we play as a group there are parts for everyone, even if I have to write a new part that just consists of Bs, As and Gs for someone who's only been playing a few weeks. Part of the problem with waiting until you're 'good enough' to play with others is that when you do reach that stage, you don't have any experience of playing with others! In one worst case scenario, you could be Grade 8 'on paper' but only ever have worked on exam pieces and not much else, and the only ensemble playing you've done is once a year with an accompanist, whose job it is to follow your playing, whatever you do. You could be technically brilliant, but just not used to playing a part that isn't 'the tune' and listening out for how your part fits in with everyone else. You might not have a lot of experience of sight-reading. You might not have any idea how to follow a conductor. Now, none of this is the fault of the student, but it strikes me that if one of your aims is to play in an ensemble, then one of the things you really need to learn is ensemble skills. That includes experience of listening to other parts and fitting in with them. It involves getting used to playing harmony parts and thinking about how they work in the piece as a whole, being sensitive to how loud or quiet you need to play, considering how to match your articulation or phrasing to what other people are doing. You need to get used to 'keeping going' whatever happens - there's a mantra about sight-reading for exams where people are told to keep going, don't go back and correct a mistake, and this is absolutely vital if you want to keep your place in ensemble music. You need to practice keeping in time with a whole load of other people - either by following a conductor or communicating somehow as a group. And really, the only way to learn these things is to do them. Teachers can help - I do 'playing together' and 'call and response' activities in lessons from the very start, and encourage students to learn duets for us to play together, rather than just using them as a 'fun' thing to do at the end of a lesson (this blog post from David Barton Music is also well worth reading on this topic). It occurred to me a while back that tutor books often have the student playing the top line of duets, for quite a long time, and then it can be quite tricky when you ask them to try playing the bottom line - your eyes just get used to looking in the same place - so have made a point of finding duets where both parts are manageable in the early stages. I think recorded backing tracks can play a useful role here as well, for the experience of playing along with 'someone else' who isn't going to adapt to you. Individual lessons can only do so much towards this though, and just playing with other people helps to make you better at playing with other people. It's one of the reasons I run Sheffield Flute Choir and also why we have an annual summer playday where anyone can come and join in (as well as improving people's skills, the other main reason is that it's fun getting together with loads of other flute players!). Obviously, getting guidance from more experienced ensemble members and leaders can be invaluable too, and *subtle move into advertising here* that's why I've asked Carla Rees to join us for the playday this August. I've experienced Carla's ensemble-leading quite a few times now, including with the rarescale Flute Academy and I'm every time I come away feeling like I've learned something new about how to play as a group. She has some serious words of wisdom about shifting your mindset from playing like a soloist to working as a team. If you'd like to hear them, and explore a range of excellent flute ensemble repertoire at the same time, come and join us in Sheffield on August 25th for our Summer Flute Ensemble Day. Do you ever feel like the worst musician in the room/ orchestra/ world? I'm sure we've all been in situations where we feel like we're much worse than everyone else at whatever it is we're doing. Sometimes we are, actually, technically, the worst. I could recount many memories of playing various sports or games where I was the weakest, the least coordinated, the slowest runner. There was the time I played rounders with some work colleagues and everyone else was good or at least passable at it. I failed to catch anything, other than a ball to the head when I entirely misjudged how fast it was coming at me.

I have also been in musical situations where I've been the least technically-accomplished player or the least experienced. I remember sitting at the far end of a row of six flutes in a youth orchestra, feeling like everyone else was so much better than me, probably because they were. It's something I hear from a lot of other people too - they worry about playing in a group or coming to a workshop because "I'll be the worst there", "everyone is better than me". It's fairly common with adult learners, as they feel they 'should' be more accomplished simply because they're adults. I understand that worry, but if you can re-frame 'being the worst' it can help you enjoy and benefit from experiences that you might have otherwise avoided. For one thing, the language of 'better' and 'worse' is fairly unhelpful, and suggests that it's in some way a failing not to be as 'good' as someone else. It is language that sadly pervades some musical environments so it's no wonder that people feel intimidated by this sense that they're being ranked into levels of 'how good you are'. It's part of the (damaging, in my opinion) discourse of 'natural talent' that suggests you're somehow inferior if you can't currently do something. However, I think it's better to think of yourself as at a different stage on your musical journey - perhaps you started later, or you haven't had as much time to dedicate to it. It may be that some people have found solutions that work for them to problems you're still struggling with. This is all OK, and nothing to be ashamed of. If you're willing to learn and try to find solutions, then the only people who should be ashamed are those who look down on others for not being at the same stage as them. Maybe you could have practised more/ better, but it's more productive to go and do some constructive practice now than to beat yourself up about not having done it in the past. Yes, it is difficult to feel like everyone else in the room can do things that you can't. It is OK to feel like you've got a long way to go, and even a bit envious of someone else's lovely tone or amazing finger-work. But you can turn that around - see it as something to aspire to. Learn from them. And don't forget to appreciate your own skills too - maybe you can't play super-fast but you can get amazingly loud volume. Maybe you don't yet have the tone you want (if you're a flute player, that's a lifelong search!) but you can sight-read/ busk your way through most things. Maybe you aren't the best at any of these things, but you're a generally reliable, happy soul to have around in rehearsals. Whatever the case, you have your own unique qualities in your playing, and none of these things make you a better or worse person (except maybe being reliable and cheerful to be around, which is definitely a good thing). The vast majority of people will not be looking down at you because you're not a virtuoso - in fact, most will be too busy worrying about their own playing, but those who are more advanced can make things easier on other people too, by being sensitive to the fact that others might find their level of skill and/ or confidence intimidating. If you find something easy, it can feel natural to always be the one volunteering to demonstrate, or play the solo, but you can support other people by stepping back sometimes, by being supportive, offering encouragement and sharing things you've found helpful in your own learning (without sounding like a know-it-all!). Teachers can help by making their teaching constructive and encouraging, rather than a list of things that the student has done wrong. They can openly talk about the aspects of playing that they find/ have found difficult and how they've worked on them. I've written before about awareness as part of my series on being a reliable musician and I think that applies here too - be aware of how your behaviour is affecting yourself and other people, whether that's putting yourself down and grumbling about finding things too hard, or acting in a way which might make other people feel bad about themselves and their playing. And remember that how you play is not a reflection on your worth as a person! In odd bits of spare time, sitting on the bus or having a cup of tea in the evening, I really like reading the Mumsnet forums. It's such an insight into human life and people's ideas and how people can have such varying opinions on a subject and all be sure that their opinion is right. It's probably also the reason why I have such a clean washing machine, the Household section is full of some incredible wisdom. Recently I read discussions about whether a family should still pay their cleaner when they had told her not to come that week because of the snow, and about whether a childminder should still charge her clients if she was open but they'd decided not to travel to her due to the weather. Opinions were sharply divided between "if it's you that cancels, you should still pay" and "they're self-employed - if they don't do the work they don't get the money".

Similarly with music lessons, it probably often feels like a straightforward exchange - a set amount of money for a set amount of the teacher's time, a bit like buying a product. Music teachers charge different rates, in different ways, and have different policies about things like charging for cancellations, but there is a definite shift in the 'industry' towards not being paid purely for 'hours of teaching done'. I'm not entirely sure why this has come to a head so much recently. Certainly, the very recent bad weather has seen many teaching colleagues worrying about lack of income due to cancellations. But even before that, in the last few years, there have been endless conversations about the unreliability and unpredictability of a teaching income. It's been suggested that part of the issue is that music lessons aren't seen as a priority (this is a far bigger problem in education than just affecting private music teaching, but perhaps it's part of a wider trend). Of course the vast majority of our students aren't going to go on to do music as a career, but it's true that sometimes it's seen as the thing that's most expendable aside everything else they're doing. And of course, it's each individual student's/ family's choice as to how important it is to them. I'm sure most music teachers will confirm, though, that they're often asked to cancel or reschedule in favour of a sporting event or a school trip or something else. Of course it's easier to reschedule or cancel the thing that involves the individual teacher, rather than a group event, and we teachers do our best to offer alternatives where we can. However, many of us teach numerous other students (at the time of writing this I have 30+) and timetabling is a tricky art as it is, so rescheduling isn't necessarily easy. So, yes, the music teacher's heart sinks a bit when they get another text cancelling a lesson. Even if you have a cancellation policy - say 48 hours in advance of a lesson or it's chargeable - this isn't always easy to enforce and people do argue over it. We worry about how we maintain our student's progress when they're missing lessons. We worry about losing income and whether we can really afford to keep doing this job we love. It is a lovely job, at its heart, but it's also very definitely a job. For most of the teachers I know, it's not something we do 'on the side' - it's our main, or indeed sole, income. We're not like the old stereotyped image of the 'little lady piano teacher down the road' who teaches for a bit of pocket money whilst her husband pays all the bills. I've recently changed to a monthly 'subscription' system - this entitles students to me being available to teach them for a certain number of lessons per year. Rather than paying on the day or according to the number of lessons they have in a particular month, the amount for the year is split into 12 equal monthly instalments (it can easily be worked out pro-rata for people starting part-way through a year). Currently, it's 42 lessons per year for those who have weekly lessons, which allows some flexibility on both sides for planned holidays etc. Students/ parents know exactly how much they're paying every month. I know that I have a steady income, which makes it easier for me to carry on teaching as a career and devote more time and energy to the musical and educational side of it rather than the 'worrying about money' side. It's a bit like a gym membership, although students obviously can't just have a lesson any time! They are, in part, paying for me to reserve a regular space in my timetable for them - which can't easily be replaced by other paid work if they cancel a lesson. As giving them 'access' to so many lessons per year, it's also reflecting the fact that teaching is about more than just the hour a week you might spend being actively taught. If you look at a music teacher's timetable, it might look like they have lots of spare time - mine sometimes has whole mornings free and gaps between lessons! However, ask any teacher what they do with that time, and they will tell you about the admin. Just today, I've spent the whole morning sending out and replying to emails, scanning and copying documents, doing some online promotion for concerts, researching resources and arranging travel for a some training which will benefit my teaching. I travel to my students, so my teaching also includes travel time/ expenses. Teachers who don't travel have the expense of premises and more than likely buying and maintaining a piano. We need working computers, printers, scanners, and TONS of ink. We have to keep up-to-date with books, resources, instruments, methods, teaching ideas - so we have to buy things and go to conferences and do CPD courses. We have books that we'll happily lend you, but you're also partly paying for access to this library of ours. We need to pay for DBS checks, public liability insurance, professional memberships. We have to maintain good quality instruments in good working order to be able to teach you to play yours. (There's another excellent explanation of the monthly payment system and what you're paying for in Tim Topham's studio policy - he also writes in more detail for teachers about this system here.) We also do need to take time off - sometimes at short notice if we're ill (or snowed in) - and the flexibility of the subscription system allows me to make that up at a later date without doing any complicated calculations - students are assigned a 'make-up credit' which can be used against another lesson. The monthly payment system won't work for everyone - not all teachers will want to work that way. I have a handful of students who have ad-hoc lessons because their work or health circumstances mean they can't easily commit to a regular time-slot. However an individual teacher decides to charge for lessons and deal with cancellations, by having lessons with them you're agreeing to accept their policy. If you haven't read it or you argue with it, you're making it difficult for them to do their job. Mainly, we do this job because we love it, and we care about our students learning to play and enjoying music. We know that the best way to do this is through regular lessons, a commitment to learning, and a happy, committed teacher! We're only human, and in fact, being musicians, we're probably some of the more sensitive, worrying humans around. We work strange hours as it is, and we struggle to set office hours, but believe me, some of us have sleepless nights about financial worries and how to reply to those difficult emails. How can we teach well when we're stressed? So please do read your teacher's terms and conditions - we know, it's quite boring, but it saves us having to debate whether you owe us money in a particular circumstance, and spending time sending emails back and forth which could be better spent on us finding out about new and exciting pieces of music for you to learn. Please ask us if you have questions about payments, but please don't assume that your teacher is trying to scam you out of money if you think there might be a mistake. Please don't assume that just because it's a 'lovely job' we only turn up for your hour's lesson and are spending the rest of the week lazing around, occasionally leisurely polishing our washing machines. If you're having problems paying, please let us know rather than ignoring it and making us have to chase you (again, more time and awkwardness). We're musicians, there's a good chance we know exactly what it's like to be worrying about the bills! I had finished my series of blog posts on 'The Reliable Musician' - the skills and qualities that musicians need (aside from playing) to get on well when playing with other people. However, a few conversations with people about how we can actually 'teach' or pass on these skills have prompted me to write a bit more. The qualities and habits I've written about have been described by various people as 'common sense' but also as 'unwritten rules' or 'unspoken agreements' - how do we encourage our students and the other musicians we come in contact with to behave in these helpful ways?

I suppose writing a series of blog posts was part of my attempt to explain the behaviours that I think make for a good, reliable musician - behaviours that I've seen the positive results of (and the problems that the opposite can cause). I can only hope that people visit my blog and/ or see them pop up on social media and find them useful. If there's a sense that these are some sort of secret, hidden rules that only (some) musicians know about though, maybe we need to state them more clearly. We can talk to our students about these things - we don't need to present them with a list of rules for going to rehearsals, but maybe if it's the first time they've joined an ensemble, there's no harm in reminding them that they need to take a pencil, might need a music stand etc. It's worth us talking about our own rehearsals/ playing work and how we prepare for these. We can model good behaviour by responding to their enquiries promptly and talking about/ demonstrating how we work on the music we need to practise. We can encourage good habits by stating our expectations of our students and ensemble members - if we're arranging an event we can give out information sheets, or emails, reinforced by verbal instructions if needed, about what people need to bring and how early they need to be there. We can give clear directions, such as needing to respond with availability by a certain date, or what people need to do if they can't make a rehearsal. We could talk more openly about the behaviours that make us want to work with people, and be less tolerant of the ones that don't. But it can be difficult to challenge someone's behaviour, especially if it's gone unchallenged for a long time. Sometimes musicians will be 'not invited back' if people find them unreliable, but often the link between the unreliability and the lack of future work isn't made clear - and how does anyone learn from that? Do we worry that people will be upset, or that they'll be angry and defensive if we tell them what the problem is? Musicians are renowned for worrying about their reputation - which is usually based on how 'good' they are, but perhaps they need to worry more about their character - taking this to be their habits and behaviours around working with other people. And if we get frustrated by the way people behave, then we need to think about the best ways to influence that behaviour and somehow teach/ explain/ demonstrate how their habits affect other people, and therefore inevitably themselves. One of the best analogies I've ever read for how music lessons should be is in 'The Perfect Wrong Note' by William Westney - which compares the process to the student working on trying to get a machine working. They've tried all sorts and had some success, but when it comes to their lesson, they bundle up all the loose bits and bring them along to show their teacher - "I've managed to get this part fitted in here and working, but I can't figure out how these go together or how to make them turn round". Lessons are the place to get help with the things that you can't do or aren't sure about. I'm also always happy for students to text or email me between lessons if they have any questions - it might be something that's easily fixed with a quick answer or I can give you some ideas to try out in your practice. You can text me a picture of something in your music, asking "what's this again?!" or if you're really struggling to find a recording, I might have something I can bring along to your next lesson, or I might be able to record a quick mp3 of a few bars to help you out.

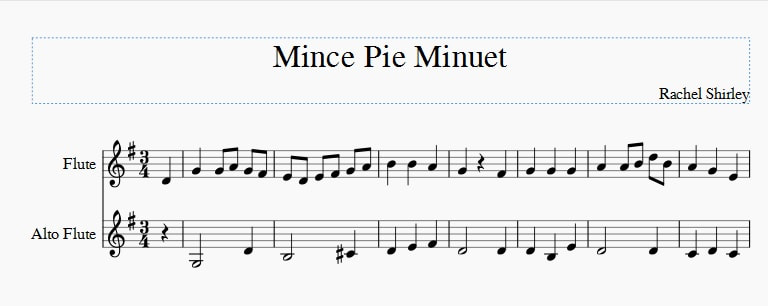

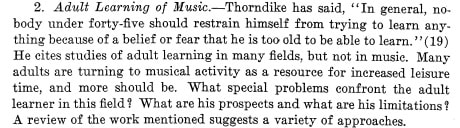

But music teachers can't be available 24/7 and there are other things you can do between lessons to help you figure out the bits you're not sure about. I still have occasional lessons, but part of learning music is also 'learning how to learn' and finding out where to go if you're puzzling over a problem. When you're used to looking these things up on a regular basis, it becomes habit, but if you're not and you're in the middle of a practice session thinking "help! I have no idea what to do!" then it can be difficult to know where to start. So I thought it would be useful to put together a page of resources in one place, to help students if they're stuck with something between lessons. There's a bit of a flute focus, but most of it will be handy for players of any instrument. (Side note: a lot of these are online resources, and a few people have mentioned to me that they get distracted if they have their phone/ computer nearby whilst practising. If that's the case, then maybe 'allow' yourself to have your phone/ computer/ technology item of choice only for the first or last, say, ten minutes of your practice session, when you're dealing with the specific issue that you need to look up. You might want to stop notifications from popping up for that time, if they're likely to lead you astray. Then you can either put it away for the rest of your practice session, or if you use it at the end you can finish, pack up your instrument and go and check all your social media if that's what you want to do!). How does this piece go again? As much as the sheet music tells us 'how a piece goes', there are times where we all get stuck with how something is supposed to sound. Some books come with CDs or downloads of the tracks which can help with this, but if they don't then YouTube is usually my first stop. As with any online resource, you need to exercise some care - professional performances are more likely to be accurate, but that's not to say there aren't lots of brilliant home recordings out there too. But do be aware that what you hear might not be exactly what's on the page, whether that's through error or intentional interpretations of the piece. Other online music resources like Apple Music and Spotify are great too, and it can be helpful to listen to different versions of the same piece to get ideas about how to play it. If you can't find the exact piece, then even looking up something in the same style can give you ideas about how to play it, for example looking up Minuets or Waltzes to give you a feel for those sort of pieces. How do I do that? YouTube also has some great instructional videos. If you're struggling with how to do something in particular on your instrument, it's worth a search to see if anyone's put up a video about it. Now, you will possibly find varying and even completely conflicting views on aspects of technique, but I always encourage students to experiment - so try a few out and see what gives you the results you're looking for, remembering that there is no such thing as "one size fits all" when it comes to playing an instrument. You'll also find lots of web sites written by flute players and teachers, with advice about technique and about particular pieces. Jennifer Cluff's site has a wealth of ideas and answers to questions sent in by players. Paul Edmund-Davies' Simply Flute has some great exercises accompanied by videos showing how to work on them. If you're exploring how to play alto or bass flute, have a look at these blog posts by Carla Rees on different aspects of the low flutes. If you're looking at some of the different techniques on the flute besides 'normal' notes, I think the short video tutorials at Flute Colors are brilliant - whether you've come across one of these 'extended techniques' in a piece, or you just want to try out making a different sound! You can also try asking on online forums or Facebook groups - there are plenty out there for general music and for specific instruments, which also have the benefit of acting as a community where you can chat to and compare notes with other people learning. Again, you'll probably get differing views on the same issue, so it pays to be open-minded to trying different possible solutions. I love arriving at a lesson to a student telling me they've been reading different ideas about how to do something - we can then play around with these in their lesson and see what works! How do I play that note? If you're stuck on how to play a particular note, fingering charts are what you need. You can often find these in the back/ middle of tutor books, or more detailed books (including alternative fingerings and trills) are available. You can also buy fingering charts that are small enough to carry around in your bag or flute case. If you prefer to go online, I like the charts at WFG and FingerCharts (which also has a really handy app for Apple and Android). What does that word mean? What is that squiggly sign on the music? If you're not sure or can't remember what an instruction on your sheet music means, whether it's a foreign musical term or a sign for an ornament, there are a few places you can look these up. If it's a word, just Googling can work (although it's often worth adding 'music' to your search term as the usage in music might be slightly different to the everyday translation). Likewise if you look up 'musical ornaments' you'll find lots of pages explaining what the symbols mean, such as the BBC GCSE Music resources. For generally improving your music theory knowledge, MyMusicTheory is a brilliant site with clear explanations and exercises to work through. If you prefer to have a reference book to hand, the classic is the ABRSM 'Pink Book' (and it's second volume, the blue one). Still stuck? Ask! Ask your teacher, ask a friend who plays an instrument, ask the other people in your band or orchestra. Lessons are just part of the picture of learning music, and you can learn as much from other people (which is one of the reasons why playing in a group is so good for your progress, as well as being enjoyable and social!). People learn in different ways, with different methods and pick up skills in different orders, so they might know something you haven't learnt yet, or have tried a different technique for whatever it is you're trying to do. And the same applies to you too - you might be able to answer someone else's question or suggest a solution to something that's been puzzling them. Or maybe you'll be able to work it out between you! Do you have any resources that you turn to when you're stuck? More suggestions are always welcome!  Sometimes musicians are guilty of not thinking much about composers. We open a book and there's some music printed there, and we play how we think it goes. We might puzzle over the composer's 'intentions' and debate whether it's important to play exactly what they 'meant', and how we can possibly know that if the composer lived 300 years ago. I have never considered myself a composer. I've written short compositions as answers to theory exam questions. I wrote a flute and piano piece for a competition run by Flutewise magazine many years ago (it got some nice feedback on the melody but I forgot to leave the flute player enough room to breathe!). I wrote some bits and pieces for composition classes at Uni, and my setting of the words to 'Down in Yon Forest' was performed by the University choir at the Christmas service one year. I started work on an LCM composition diploma a few years back, arranging a piano piece for a wind trio. I've arranged a few of the local Sheffield carols for our flute choir. I'm still not a composer though. There's a risk of a bit of a 'them and us' feeling between musicians and composers. We could see the people who write the music as some sort of anonymous authority figures, imagining them to create these perfect finished pieces out of nowhere. Rather like the idea that 'good' musicians can just perform a piece first time, it's quite off-putting if you think about composing and imagine that you can only do it if masterpieces pour instantly from your pen (or computer software). Both things are a process and involve hard work! I've been lucky enough to work closely with some composers over the last couple of years. At Sheffield Flute Choir, we've worked with local composers Tim Knight and Jenny Jackson as they produced new works for flutes. Jenny ran a workshop on composition for flute this year, where I got to work with budding composers as they learned about the composing process and produced a piece for solo flute in just one day - this was an amazing experience to work with people writing music from the very start, to talk about how they got what they wanted it to sound like onto the page, and how I as a player interpreted what was written down. I've played brand new works by all of the Platform Four composers, seeing pieces evolve as rehearsals progress. I've met the lovely Keri from Masquerade Music, and the equally lovely Rob and Lynne from Forton Music, who are all running small businesses writing, arranging and publishing music for woodwind. I've performed pieces by David Barton - you can find us playing his 'Imagination' on YouTube here. I've also recently been reviewing new sheet music for Pan, the British Flute Society magazine, from publishers big and small - and it's struck me that it's a great privilege to be trying out this music that composers have sent out into the world, hoping that we like it. While we might worry about 'getting the composer's music right', they worry about whether it's playable, enjoyable, too hard, too easy, ready to be heard. Social media also brings us closer to composers, hearing about the process of writing music (and all the other things going in their lives at the same time too!) - it's through social media that I've discovered the exciting new flute music of Nicole Chamberlain and the utterly joyous 'An Harmonic Disquisition Upon Various Types of Cheese' for piccolo quartet by Brandon Nelson. I've recently read Brandon's new book 'Writing and Living in the Real World: Advice for Young Composers'. This is an excellent guide for anyone who wants to write music as a career (or part of a career). It isn't about how to compose - other than some good ideas about time management and motivation - but covers the practical side of getting your music out there: publishing and marketing. There's also some very thoughtful chapters on originality, creativity and artistic identity which are worth reading by anyone who has or wants to have a creative career. And far from the idea of the composer up in their ivory tower magically creating masterpieces, it emphasises the importance of sitting down and putting the work in: "Keep writing. Even on days you "just don't feel it"." So, back to being a composer (or not). I haven't found myself struck by inspiration out of nowhere. However, I have found myself in need of more duets to use with my students - ensemble playing is so important (and fun!) and I'm endlessly trying to find enough pieces to fill the gap between easy and difficult duets. Many of the composers/ publishers above have some great books, but I always want more. I've also had a few conversations this year about the fact that more of us than ever have 'big' flutes (alto, in particular, and bass) and we always need more things to play on those. I want music that will work if I take my alto along to a lesson - both for me to play and to introduce students to it when they're ready. So, I decided to try and write a few duets to fill those gaps. I'd been doing a lot of work with students on discovering the Baroque dance forms that appear in so many flute pieces, so those seemed like a good place to start - writing my own simple versions of those. I used the key signatures and rhythms that students are familiar with from around Grade 3 standard. I deliberately didn't add any dynamics or articulation so they could practise working out their own in preparation for real Baroque music. And because I like to tie music theory in to what we're working on, the harmonies are mostly nice and straightforward so that students at that level can analyse it and figure out the chords and cadences. So this is very much composing with a particular (educational) purpose in mind, but they're hopefully enjoyable tunes too! If anyone else thinks they would find them useful for teaching or just playing, I've uploaded a few for sale at Sheet Music Plus, including a silly seasonal one... and yes, there is a bit of a theme to the titles! To the real composers I know, have met, have worked with, follow on Twitter, or just encounter your music - thank you for your hard work, persistence and bravery in sharing your work with the world - we might grumble about you sometimes ("you want me to play WHAT?!") but where would we be without you? The other day, I came across this article from 1938 entitled 'Needed Research in Music Education'. Leaving aside the "nobody under forty-five" bit (lets just make that "nobody"!), it's another to add to my collection of quotes which basically say "someone should be researching adult learning in music". They pop up in the literature every few years, whilst actual research into adult learning appears at a slow trickle. They're one of the things that keep me going with my research, when the thought of the long, slow process seems overwhelming.

Articles about adults learning music appear in the more mainstream press now and then too - why it's good for our (ageing) brains, the story of someone deciding to take up the piano after dreaming of playing for years. I was pleased to spot a magazine article this week about the benefits of learning music as an adult, but then rapidly disappointed by lines about "demoralising (or just plain boring) school lessons" and "shake off the shackles of childhood piano lessons and start having fun". There's nothing necessarily wrong with teaching yourself or making use of YouTube videos, as the article suggests, but this disparaging view of music teaching got my back up. Yes, there are boring/ miserable lessons/ teachers, but there are so many teachers that I know who are trying their best to make learning music enjoyable and engaging for all ages. Although the article pushes the social benefits of music, it takes confidence to go and join a group - I'm not sure how easy some people will find it to step out from behind their computer and go out to play in public. That can be something that a teacher can help to 'hold your hand' through, playing with you in lessons, arranging informal opportunities for you to play with and in front of other people, suggesting suitable ensembles to try out. Going along to lessons is a social interaction in itself, and don't we spend enough time in front of a screen as it is?! I have a couple of other issues with dependence on video lessons - firstly, there isn't someone there observing you and helping you out. I've come across adult learners who've struggled with teaching themselves through online courses, because they're trying to follow a set of 'one size fits all' instructions. The instrument hasn't been set up properly for their particular body shape and size, their hand position is all wrong for the length of their fingers, and they're wondering why it doesn't sound right, and even more worryingly, it feels uncomfortable. Look at just a few clips of professional flute players and you'll see variations in how they use their hands, arms, mouths - because bodies aren't all made the same! This is something that a teacher can help to work out, helping you to avoid injuring yourself at the same time (it might seem difficult to injure yourself with an instrument but the damage that musicians do to their bodies is a big issue - if you're doing a repetitive movement many times, you want to be doing it in the best way possible). They're also there to help with the mental and emotional aspects of learning - supporting you through the frustrating times and helping you navigate the process of learning music alongside all the other challenges in life. I entirely understand that it costs more to take lessons than to watch YouTube for nothing (and clearly I have a vested interest in people taking lessons!), but I wonder whether sometimes 'free' isn't the bargain it seems to be. My other issue is an apparent obsession with speed (of learning, not of playing!) - online teaching resources I've seen use phrases like "fast-track your results". One, specifically for adults, promises to "skip the simplistic and slow approaches used with children and will get you playing in no time". While I'm not doubting - and research, including my own, suggests - that adults need some different approaches to children, I am wondering what's so wrong with 'simplistic and slow'? I certainly see a desire for quick results in many students (as much in children as adults, I would say), but surely there is nothing wrong with taking your time? As well as getting away from the screen, why can't learning music also be a change in pace from the rest of life? I'm reminded of the 'slow food' movement which celebrates traditional methods of growing and cooking, and of the trend for mindfulness which encourages people to slow down and observe. Why should learning music be a race? Why shouldn't we enjoy the gradual process, and celebrate the beauty of playing something simple well. Perhaps adults do want quick results. Maybe they don't want teachers (although my research suggest that that plenty of them do, and that the teacher-student relationship is really important). I suspect that what really works well for most learners, whatever their age, is a combination of approaches - individual lessons, playing with groups, making use of some online resources, experimenting on their own. We need to look at what benefits learners most - musically, but also mentally and physically - is it the quick fix that seems initially most appealing, or is it taking your time and immersing yourself in the long, wonderful process of learning? We could say that 'slow and steady wins the race' but I think what's most important is that it isn't a race! I've been a member of the Incorporated Society of Musicians (ISM) since I started teaching. Essentially there's a choice of two 'unions' for musicians, the ISM and the Musicians' Union, both offering support, advice, legal protection, training, online communities and real-life meet-ups. I've benefited from the ISM's resources for teachers - I use a version of their teaching contract - and I couldn't (legally) do my job without their Public Liability Insurance (although I've thankfully never had to claim on it!). They run regular webinars which have given me some interesting food for thought on topics such as 'teaching in the digital age' (how do we keep the attention of children who are used to social media and computer games?), career planning and psychological wellbeing for musicians.

Their blog is a great resource of ideas and opinions from different musicians, too, and I've particularly enjoyed the new Teacher Focus series, where a private teacher writes about their own job, thoughts and experiences. So I was very happy to answer a call for more contributions to this series, and reflect on my background, principles of teaching and hopes for the future - you can read my post at https://www.ism.org/blog/private-teacher-focus-rachel-shirley. |

Keep in touch

I have an email newsletter where I share my latest blog posts, news from the flute and wider musical world, my current projects, and things I've found that I think are interesting and useful and would love to share with you. Expect lots about music and education, plus the occasional dip into research, language, freelance life, gardening and other nice things. Sign up below! Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed