|

A reporter once asked the celebrated orchestra conductor Leonard Bernstein what was the most difficult instrument to play. "Second fiddle! I can always get plenty of first violinists, but to find one who plays second violin with as much enthusiasm, or second French horn, or second flute, now that's a problem. And yet if no one plays second, we have no harmony.” It's supposed to be the pinnacle of ensemble playing, being on the 'first' part. It means you're the best, you can play all the hard stuff, you can do the twiddly bits. It's just one step down from being a soloist. It's fascinating watching the jostling for position - both physically and metaphorically - that can happen in some groups. So-and-so should play first because they've been here the longest. Whatshername should do it because she's 'better'. Ask a big group of musicians to allocate themselves to parts and some will rush to either end - they want to play first because they're 'good enough', or they want to play fourth or fifth because they're 'not good enough'. They want to show off or they want to hide. They'll insist on playing the top part or they'll step back and offer it to someone who they think is better than them - there can be a game of "no, no, after you"... "no, no, I insist". This ranking of musicianship is ingrained in us from the early stages of playing - 'first' is something to aim for, it's where the better players end up. And it's true that first parts tend to be more technically challenging and mostly, in a higher register, which is something that flute players, at least, learn as we get more advanced. But that doesn't mean that playing second (or other parts in different ensembles, such as a flute choir) is easy or any less valuable. You might not get the high twiddly bits, but you might have a vital harmony part. Can you blast out those lower notes so they blend with the higher ones elsewhere rather than being drowned out by them? Can you maintain a repeated pattern on the same couple of notes for ages without it losing energy? Can you handle playing on the off-beats for ages? Can you concentrate to count for lots of bars rest?! Can you match your sound to that of the person playing first? Someone once described the role of orchestral flutes to me as the first providing the 'colour' and the second having to adapt into that first players sound - that's quite a skill. Sometimes the second or third part will be doing something completely different to the first, and having to blend with the violins or the French horns. As individual instrumentalists, our education doesn't always prepare us for this - flute players, for example, mostly learn solo repertoire. We're used to playing the tune (I've had transfer students who could only play the top line of duets because they'd never played the second part - they found it such a challenge visually to follow the lower line!). So when we join an ensemble, we might opt for what seems like the 'easier' part, but then discover that it isn't that at all. We're not accustomed to playing harmony parts, to making so much use of our low notes, to playing parts with so many gaps in them. Equally, ensemble directors might order the parts with the most experienced players on first and least experienced on 'lower' parts, and find the balance really not working. I wish we could get away from this idea of first as better. One of my very accomplished flute colleagues likes to sit in different places at our ensemble rehearsals, and noted that some less advanced players asked why she was "lowering herself" to play third or fourth flute. But it's enjoyable, good for your playing, and great for exercising different skills to mix it up. In the orchestra I play with, we have three regular flautists, and we rotate around parts, depending on who would prefer to play what and playing to our strengths. For our next season, we're playing first for one concert each, and second for one half of each of the other concerts (with the occasional piece that needs all three). We figured it out through an online chat whilst one of our number was sunning herself on holiday, and I was on my sofa. We put forward our requests to play certain parts because of musical preferences, because we wanted to be in or out of our comfort zone, and so we could have a quieter time when other parts of our lives were hectic. It works - nobody feels left out or under pressure. It keeps us on our toes and makes us better players because we all get a turn at the twiddly bits, the harmony bits, the counting, the matching our sound to other people's. So, I guess this is an appeal to players, not to get hung up on the numbers. The composer wrote two parts or seven parts because they wanted them all, so they're all important. Try them all. Feel how glorious it is to play a bassline, to harmonise under the melody. Twiddle away on top or embrace those syncopated rhythms in the middle. And to teachers, too - get your students playing duets with you, and group pieces with each other, right from the start. Help them to be a flexible player who can happily get stuck in with any part of an ensemble and do a great job of it. A few links:

This article by flautist Rachel Taylor Geier has a great summary of the skills needed to play second flute. An excellent blog post by David Barton Music about the role of duets in lessons. "Who's on first?" - nothing to do with music but I was introduced to this comedy sketch last year, it inspired the title of this post, and the play on words makes me laugh so much!

0 Comments

Do you ever feel like the worst musician in the room/ orchestra/ world? I'm sure we've all been in situations where we feel like we're much worse than everyone else at whatever it is we're doing. Sometimes we are, actually, technically, the worst. I could recount many memories of playing various sports or games where I was the weakest, the least coordinated, the slowest runner. There was the time I played rounders with some work colleagues and everyone else was good or at least passable at it. I failed to catch anything, other than a ball to the head when I entirely misjudged how fast it was coming at me.

I have also been in musical situations where I've been the least technically-accomplished player or the least experienced. I remember sitting at the far end of a row of six flutes in a youth orchestra, feeling like everyone else was so much better than me, probably because they were. It's something I hear from a lot of other people too - they worry about playing in a group or coming to a workshop because "I'll be the worst there", "everyone is better than me". It's fairly common with adult learners, as they feel they 'should' be more accomplished simply because they're adults. I understand that worry, but if you can re-frame 'being the worst' it can help you enjoy and benefit from experiences that you might have otherwise avoided. For one thing, the language of 'better' and 'worse' is fairly unhelpful, and suggests that it's in some way a failing not to be as 'good' as someone else. It is language that sadly pervades some musical environments so it's no wonder that people feel intimidated by this sense that they're being ranked into levels of 'how good you are'. It's part of the (damaging, in my opinion) discourse of 'natural talent' that suggests you're somehow inferior if you can't currently do something. However, I think it's better to think of yourself as at a different stage on your musical journey - perhaps you started later, or you haven't had as much time to dedicate to it. It may be that some people have found solutions that work for them to problems you're still struggling with. This is all OK, and nothing to be ashamed of. If you're willing to learn and try to find solutions, then the only people who should be ashamed are those who look down on others for not being at the same stage as them. Maybe you could have practised more/ better, but it's more productive to go and do some constructive practice now than to beat yourself up about not having done it in the past. Yes, it is difficult to feel like everyone else in the room can do things that you can't. It is OK to feel like you've got a long way to go, and even a bit envious of someone else's lovely tone or amazing finger-work. But you can turn that around - see it as something to aspire to. Learn from them. And don't forget to appreciate your own skills too - maybe you can't play super-fast but you can get amazingly loud volume. Maybe you don't yet have the tone you want (if you're a flute player, that's a lifelong search!) but you can sight-read/ busk your way through most things. Maybe you aren't the best at any of these things, but you're a generally reliable, happy soul to have around in rehearsals. Whatever the case, you have your own unique qualities in your playing, and none of these things make you a better or worse person (except maybe being reliable and cheerful to be around, which is definitely a good thing). The vast majority of people will not be looking down at you because you're not a virtuoso - in fact, most will be too busy worrying about their own playing, but those who are more advanced can make things easier on other people too, by being sensitive to the fact that others might find their level of skill and/ or confidence intimidating. If you find something easy, it can feel natural to always be the one volunteering to demonstrate, or play the solo, but you can support other people by stepping back sometimes, by being supportive, offering encouragement and sharing things you've found helpful in your own learning (without sounding like a know-it-all!). Teachers can help by making their teaching constructive and encouraging, rather than a list of things that the student has done wrong. They can openly talk about the aspects of playing that they find/ have found difficult and how they've worked on them. I've written before about awareness as part of my series on being a reliable musician and I think that applies here too - be aware of how your behaviour is affecting yourself and other people, whether that's putting yourself down and grumbling about finding things too hard, or acting in a way which might make other people feel bad about themselves and their playing. And remember that how you play is not a reflection on your worth as a person! In odd bits of spare time, sitting on the bus or having a cup of tea in the evening, I really like reading the Mumsnet forums. It's such an insight into human life and people's ideas and how people can have such varying opinions on a subject and all be sure that their opinion is right. It's probably also the reason why I have such a clean washing machine, the Household section is full of some incredible wisdom. Recently I read discussions about whether a family should still pay their cleaner when they had told her not to come that week because of the snow, and about whether a childminder should still charge her clients if she was open but they'd decided not to travel to her due to the weather. Opinions were sharply divided between "if it's you that cancels, you should still pay" and "they're self-employed - if they don't do the work they don't get the money".

Similarly with music lessons, it probably often feels like a straightforward exchange - a set amount of money for a set amount of the teacher's time, a bit like buying a product. Music teachers charge different rates, in different ways, and have different policies about things like charging for cancellations, but there is a definite shift in the 'industry' towards not being paid purely for 'hours of teaching done'. I'm not entirely sure why this has come to a head so much recently. Certainly, the very recent bad weather has seen many teaching colleagues worrying about lack of income due to cancellations. But even before that, in the last few years, there have been endless conversations about the unreliability and unpredictability of a teaching income. It's been suggested that part of the issue is that music lessons aren't seen as a priority (this is a far bigger problem in education than just affecting private music teaching, but perhaps it's part of a wider trend). Of course the vast majority of our students aren't going to go on to do music as a career, but it's true that sometimes it's seen as the thing that's most expendable aside everything else they're doing. And of course, it's each individual student's/ family's choice as to how important it is to them. I'm sure most music teachers will confirm, though, that they're often asked to cancel or reschedule in favour of a sporting event or a school trip or something else. Of course it's easier to reschedule or cancel the thing that involves the individual teacher, rather than a group event, and we teachers do our best to offer alternatives where we can. However, many of us teach numerous other students (at the time of writing this I have 30+) and timetabling is a tricky art as it is, so rescheduling isn't necessarily easy. So, yes, the music teacher's heart sinks a bit when they get another text cancelling a lesson. Even if you have a cancellation policy - say 48 hours in advance of a lesson or it's chargeable - this isn't always easy to enforce and people do argue over it. We worry about how we maintain our student's progress when they're missing lessons. We worry about losing income and whether we can really afford to keep doing this job we love. It is a lovely job, at its heart, but it's also very definitely a job. For most of the teachers I know, it's not something we do 'on the side' - it's our main, or indeed sole, income. We're not like the old stereotyped image of the 'little lady piano teacher down the road' who teaches for a bit of pocket money whilst her husband pays all the bills. I've recently changed to a monthly 'subscription' system - this entitles students to me being available to teach them for a certain number of lessons per year. Rather than paying on the day or according to the number of lessons they have in a particular month, the amount for the year is split into 12 equal monthly instalments (it can easily be worked out pro-rata for people starting part-way through a year). Currently, it's 42 lessons per year for those who have weekly lessons, which allows some flexibility on both sides for planned holidays etc. Students/ parents know exactly how much they're paying every month. I know that I have a steady income, which makes it easier for me to carry on teaching as a career and devote more time and energy to the musical and educational side of it rather than the 'worrying about money' side. It's a bit like a gym membership, although students obviously can't just have a lesson any time! They are, in part, paying for me to reserve a regular space in my timetable for them - which can't easily be replaced by other paid work if they cancel a lesson. As giving them 'access' to so many lessons per year, it's also reflecting the fact that teaching is about more than just the hour a week you might spend being actively taught. If you look at a music teacher's timetable, it might look like they have lots of spare time - mine sometimes has whole mornings free and gaps between lessons! However, ask any teacher what they do with that time, and they will tell you about the admin. Just today, I've spent the whole morning sending out and replying to emails, scanning and copying documents, doing some online promotion for concerts, researching resources and arranging travel for a some training which will benefit my teaching. I travel to my students, so my teaching also includes travel time/ expenses. Teachers who don't travel have the expense of premises and more than likely buying and maintaining a piano. We need working computers, printers, scanners, and TONS of ink. We have to keep up-to-date with books, resources, instruments, methods, teaching ideas - so we have to buy things and go to conferences and do CPD courses. We have books that we'll happily lend you, but you're also partly paying for access to this library of ours. We need to pay for DBS checks, public liability insurance, professional memberships. We have to maintain good quality instruments in good working order to be able to teach you to play yours. (There's another excellent explanation of the monthly payment system and what you're paying for in Tim Topham's studio policy - he also writes in more detail for teachers about this system here.) We also do need to take time off - sometimes at short notice if we're ill (or snowed in) - and the flexibility of the subscription system allows me to make that up at a later date without doing any complicated calculations - students are assigned a 'make-up credit' which can be used against another lesson. The monthly payment system won't work for everyone - not all teachers will want to work that way. I have a handful of students who have ad-hoc lessons because their work or health circumstances mean they can't easily commit to a regular time-slot. However an individual teacher decides to charge for lessons and deal with cancellations, by having lessons with them you're agreeing to accept their policy. If you haven't read it or you argue with it, you're making it difficult for them to do their job. Mainly, we do this job because we love it, and we care about our students learning to play and enjoying music. We know that the best way to do this is through regular lessons, a commitment to learning, and a happy, committed teacher! We're only human, and in fact, being musicians, we're probably some of the more sensitive, worrying humans around. We work strange hours as it is, and we struggle to set office hours, but believe me, some of us have sleepless nights about financial worries and how to reply to those difficult emails. How can we teach well when we're stressed? So please do read your teacher's terms and conditions - we know, it's quite boring, but it saves us having to debate whether you owe us money in a particular circumstance, and spending time sending emails back and forth which could be better spent on us finding out about new and exciting pieces of music for you to learn. Please ask us if you have questions about payments, but please don't assume that your teacher is trying to scam you out of money if you think there might be a mistake. Please don't assume that just because it's a 'lovely job' we only turn up for your hour's lesson and are spending the rest of the week lazing around, occasionally leisurely polishing our washing machines. If you're having problems paying, please let us know rather than ignoring it and making us have to chase you (again, more time and awkwardness). We're musicians, there's a good chance we know exactly what it's like to be worrying about the bills! One of the best analogies I've ever read for how music lessons should be is in 'The Perfect Wrong Note' by William Westney - which compares the process to the student working on trying to get a machine working. They've tried all sorts and had some success, but when it comes to their lesson, they bundle up all the loose bits and bring them along to show their teacher - "I've managed to get this part fitted in here and working, but I can't figure out how these go together or how to make them turn round". Lessons are the place to get help with the things that you can't do or aren't sure about. I'm also always happy for students to text or email me between lessons if they have any questions - it might be something that's easily fixed with a quick answer or I can give you some ideas to try out in your practice. You can text me a picture of something in your music, asking "what's this again?!" or if you're really struggling to find a recording, I might have something I can bring along to your next lesson, or I might be able to record a quick mp3 of a few bars to help you out.

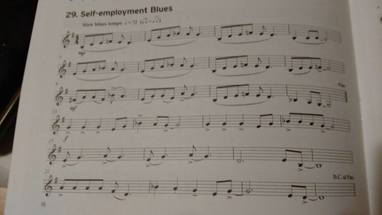

But music teachers can't be available 24/7 and there are other things you can do between lessons to help you figure out the bits you're not sure about. I still have occasional lessons, but part of learning music is also 'learning how to learn' and finding out where to go if you're puzzling over a problem. When you're used to looking these things up on a regular basis, it becomes habit, but if you're not and you're in the middle of a practice session thinking "help! I have no idea what to do!" then it can be difficult to know where to start. So I thought it would be useful to put together a page of resources in one place, to help students if they're stuck with something between lessons. There's a bit of a flute focus, but most of it will be handy for players of any instrument. (Side note: a lot of these are online resources, and a few people have mentioned to me that they get distracted if they have their phone/ computer nearby whilst practising. If that's the case, then maybe 'allow' yourself to have your phone/ computer/ technology item of choice only for the first or last, say, ten minutes of your practice session, when you're dealing with the specific issue that you need to look up. You might want to stop notifications from popping up for that time, if they're likely to lead you astray. Then you can either put it away for the rest of your practice session, or if you use it at the end you can finish, pack up your instrument and go and check all your social media if that's what you want to do!). How does this piece go again? As much as the sheet music tells us 'how a piece goes', there are times where we all get stuck with how something is supposed to sound. Some books come with CDs or downloads of the tracks which can help with this, but if they don't then YouTube is usually my first stop. As with any online resource, you need to exercise some care - professional performances are more likely to be accurate, but that's not to say there aren't lots of brilliant home recordings out there too. But do be aware that what you hear might not be exactly what's on the page, whether that's through error or intentional interpretations of the piece. Other online music resources like Apple Music and Spotify are great too, and it can be helpful to listen to different versions of the same piece to get ideas about how to play it. If you can't find the exact piece, then even looking up something in the same style can give you ideas about how to play it, for example looking up Minuets or Waltzes to give you a feel for those sort of pieces. How do I do that? YouTube also has some great instructional videos. If you're struggling with how to do something in particular on your instrument, it's worth a search to see if anyone's put up a video about it. Now, you will possibly find varying and even completely conflicting views on aspects of technique, but I always encourage students to experiment - so try a few out and see what gives you the results you're looking for, remembering that there is no such thing as "one size fits all" when it comes to playing an instrument. You'll also find lots of web sites written by flute players and teachers, with advice about technique and about particular pieces. Jennifer Cluff's site has a wealth of ideas and answers to questions sent in by players. Paul Edmund-Davies' Simply Flute has some great exercises accompanied by videos showing how to work on them. If you're exploring how to play alto or bass flute, have a look at these blog posts by Carla Rees on different aspects of the low flutes. If you're looking at some of the different techniques on the flute besides 'normal' notes, I think the short video tutorials at Flute Colors are brilliant - whether you've come across one of these 'extended techniques' in a piece, or you just want to try out making a different sound! You can also try asking on online forums or Facebook groups - there are plenty out there for general music and for specific instruments, which also have the benefit of acting as a community where you can chat to and compare notes with other people learning. Again, you'll probably get differing views on the same issue, so it pays to be open-minded to trying different possible solutions. I love arriving at a lesson to a student telling me they've been reading different ideas about how to do something - we can then play around with these in their lesson and see what works! How do I play that note? If you're stuck on how to play a particular note, fingering charts are what you need. You can often find these in the back/ middle of tutor books, or more detailed books (including alternative fingerings and trills) are available. You can also buy fingering charts that are small enough to carry around in your bag or flute case. If you prefer to go online, I like the charts at WFG and FingerCharts (which also has a really handy app for Apple and Android). What does that word mean? What is that squiggly sign on the music? If you're not sure or can't remember what an instruction on your sheet music means, whether it's a foreign musical term or a sign for an ornament, there are a few places you can look these up. If it's a word, just Googling can work (although it's often worth adding 'music' to your search term as the usage in music might be slightly different to the everyday translation). Likewise if you look up 'musical ornaments' you'll find lots of pages explaining what the symbols mean, such as the BBC GCSE Music resources. For generally improving your music theory knowledge, MyMusicTheory is a brilliant site with clear explanations and exercises to work through. If you prefer to have a reference book to hand, the classic is the ABRSM 'Pink Book' (and it's second volume, the blue one). Still stuck? Ask! Ask your teacher, ask a friend who plays an instrument, ask the other people in your band or orchestra. Lessons are just part of the picture of learning music, and you can learn as much from other people (which is one of the reasons why playing in a group is so good for your progress, as well as being enjoyable and social!). People learn in different ways, with different methods and pick up skills in different orders, so they might know something you haven't learnt yet, or have tried a different technique for whatever it is you're trying to do. And the same applies to you too - you might be able to answer someone else's question or suggest a solution to something that's been puzzling them. Or maybe you'll be able to work it out between you! Do you have any resources that you turn to when you're stuck? More suggestions are always welcome! The other day, I came across this article from 1938 entitled 'Needed Research in Music Education'. Leaving aside the "nobody under forty-five" bit (lets just make that "nobody"!), it's another to add to my collection of quotes which basically say "someone should be researching adult learning in music". They pop up in the literature every few years, whilst actual research into adult learning appears at a slow trickle. They're one of the things that keep me going with my research, when the thought of the long, slow process seems overwhelming.

Articles about adults learning music appear in the more mainstream press now and then too - why it's good for our (ageing) brains, the story of someone deciding to take up the piano after dreaming of playing for years. I was pleased to spot a magazine article this week about the benefits of learning music as an adult, but then rapidly disappointed by lines about "demoralising (or just plain boring) school lessons" and "shake off the shackles of childhood piano lessons and start having fun". There's nothing necessarily wrong with teaching yourself or making use of YouTube videos, as the article suggests, but this disparaging view of music teaching got my back up. Yes, there are boring/ miserable lessons/ teachers, but there are so many teachers that I know who are trying their best to make learning music enjoyable and engaging for all ages. Although the article pushes the social benefits of music, it takes confidence to go and join a group - I'm not sure how easy some people will find it to step out from behind their computer and go out to play in public. That can be something that a teacher can help to 'hold your hand' through, playing with you in lessons, arranging informal opportunities for you to play with and in front of other people, suggesting suitable ensembles to try out. Going along to lessons is a social interaction in itself, and don't we spend enough time in front of a screen as it is?! I have a couple of other issues with dependence on video lessons - firstly, there isn't someone there observing you and helping you out. I've come across adult learners who've struggled with teaching themselves through online courses, because they're trying to follow a set of 'one size fits all' instructions. The instrument hasn't been set up properly for their particular body shape and size, their hand position is all wrong for the length of their fingers, and they're wondering why it doesn't sound right, and even more worryingly, it feels uncomfortable. Look at just a few clips of professional flute players and you'll see variations in how they use their hands, arms, mouths - because bodies aren't all made the same! This is something that a teacher can help to work out, helping you to avoid injuring yourself at the same time (it might seem difficult to injure yourself with an instrument but the damage that musicians do to their bodies is a big issue - if you're doing a repetitive movement many times, you want to be doing it in the best way possible). They're also there to help with the mental and emotional aspects of learning - supporting you through the frustrating times and helping you navigate the process of learning music alongside all the other challenges in life. I entirely understand that it costs more to take lessons than to watch YouTube for nothing (and clearly I have a vested interest in people taking lessons!), but I wonder whether sometimes 'free' isn't the bargain it seems to be. My other issue is an apparent obsession with speed (of learning, not of playing!) - online teaching resources I've seen use phrases like "fast-track your results". One, specifically for adults, promises to "skip the simplistic and slow approaches used with children and will get you playing in no time". While I'm not doubting - and research, including my own, suggests - that adults need some different approaches to children, I am wondering what's so wrong with 'simplistic and slow'? I certainly see a desire for quick results in many students (as much in children as adults, I would say), but surely there is nothing wrong with taking your time? As well as getting away from the screen, why can't learning music also be a change in pace from the rest of life? I'm reminded of the 'slow food' movement which celebrates traditional methods of growing and cooking, and of the trend for mindfulness which encourages people to slow down and observe. Why should learning music be a race? Why shouldn't we enjoy the gradual process, and celebrate the beauty of playing something simple well. Perhaps adults do want quick results. Maybe they don't want teachers (although my research suggest that that plenty of them do, and that the teacher-student relationship is really important). I suspect that what really works well for most learners, whatever their age, is a combination of approaches - individual lessons, playing with groups, making use of some online resources, experimenting on their own. We need to look at what benefits learners most - musically, but also mentally and physically - is it the quick fix that seems initially most appealing, or is it taking your time and immersing yourself in the long, wonderful process of learning? We could say that 'slow and steady wins the race' but I think what's most important is that it isn't a race! Last night BBC Four showed the first episode of All Together Now: The Great Orchestra Challenge. Like Bake Off for musicians, this is a series where we follow several amateur orchestras through various rounds until a winner is decided (and gets to play at Proms in the Park). I wrote of my reservations about the idea when it was first announced, so it was with some hesitancy that I switched on last night.

I have to say I enjoyed most of the programme - it was lovely to hear the stories of the orchestras and some of the individuals who played and conducted them. It was particularly great to hear about how being part of the groups had enhanced people's lives, made them feel part of a community. It was fascinating to see how they worked in rehearsals, and responded to the professional coaching and intensive mentoring sessions, to hear them talk about practice (or lack of!) and the challenges of playing at a certain age, or when you've got long working hours and family to consider. Seeing/ hearing the different styles and characters of each group was really interesting, as was seeing/ hearing the progress they made over a month with the pieces they'd been challenged to learn. The competition element was kept fairly low-key, until right at the end, when each group performed their piece and there was the typical "we have to say goodbye to someone" line-up. I agree with this review from theartsdesk.com that this felt tacked-on, 'tacky and unnecessary'. Could we not have just followed the progress of all these amazing people across a few months? Could they not have all played in a concert at the end, celebrating amateur music-making and their achievements? Maybe that wouldn't have provoked as much interest as a competition. Classical music has been in the news for other reasons connected to competitions too. After the Olympics, there were questions around why there is so much more funding for sport than there is for the arts. Why 'elite' sport is seen as a good thing but 'elitism' in music isn't. That particular question grabbed my interest as a linguist - my initial thoughts are that it is in part down to the different usage of the terms. You just don't really hear anyone talking about 'elite' musicians in the same way as they do about elite athletes, even though the process of training is not actually that different or any less intense. Where the term is used, it's negative, around classical music being 'elitist' or for 'the elite' (although I have also seen some discussion about certain sports suffering from 'elitism' - debates around lack of access to particular sports to people coming from state schools, for example, which could also apply to music education in some areas). I think this is something that could make a good corpus linguistics study, to get some data around the usage of the words - maybe I'll set aside some time for a mini research project! I do wonder, though, if there is any connection between these views (and funding levels) and the fact that sport is generally competitive and music is generally not - not in quite such an obvious way, anyway. Music competitions exist, but the usual way for people to experience music is a performance/ concert, whereas the normal way of experiencing sport is to watch a competitive match or race. Do people just like the structure of competition, the tribalism of supporting a team? Is musical performance 'elitist' in a way that sporting competition (whilst involving an 'elite') is not? I was doing some updates to my website this morning, and I came across this wonderful, slightly chaotic photo from one of my student workshops/ concerts. This is a collection of my students and flute choir members, getting ready to perform to their family and friends. What I love about this photo - other than the fact it contains lots of people who I really like - is the communication between people, the concentration, the variety of people. I love that you can see players helping each other out with getting their music ready to play, supporting each other. And all the friends and relatives ready to hear the outcome of the lessons they might pay for (or keep out of the way in another room for), the practice they overhear/ endure (I know listening to someone embarking on a new octave can be less than tuneful), the enthusiastic ramblings about flute playing that they kindly listen to.

I've also been using the quieter time over the summer to sort out my home office/ sheet music library. I've finally got a pin board to display the cards that were propped up on my desk and kept falling down the back. These are from friends and students and people I've worked with. They have some lovely pictures on, but it's also a lovely boost to open them sometimes and re-read the messages. Some of them tell me about the things that really helped them and remind me how important it is that students get the support they need, not just from me, but from all sorts of people. There's an African proverb that "it takes a whole village to raise a child" and I think the same is true of raising a happy, successful musician. Students doing exams, performances or auditions don't just need lessons. My students don't just need me! They also need opportunities to practise performing (e.g. student concerts - where the other players and the audience make a huge difference). They need good accompanists who can work with them on developing their pieces into a conversation between the flute and the piano. They might need support with other aspects of exam preparation - for example, asking their accompanist to do some extra sessions on the aural tests too. I teach music theory to some students who have instrumental lessons with other teachers (they might not have time in school lessons to fit theory in, or the teacher might just not enjoy teaching it). Students might benefit from different views on an aspect of technique (sometimes just having something explained or demonstrated a different way works wonders), so workshops with other teachers and players can be really valuable. Coming to the student workshops or to a group like Flute Choir can provide different viewpoints, a chance to exchange thoughts and tips with other players, an opportunity to put skills like sightreading into action, and most importantly, encouragement from other people. When it comes to exams or performances, having people around who are calm, organised and positive really helps - good exam stewards, for example. Then there's the supportive friends, family, parents, partners, housemates, etc, mentioned above. It makes a huge difference to have people who are on your side when you're working towards a goal. One of the findings of my Master research was that adult learners really notice their support network (or lack of it) - that support can also encompass things like social media and online forums of people doing the same things, sharing their experiences of lessons and exams. And for younger students still at school, having support there is brilliant - opportunities to join groups, play in school concerts, teachers who are interested in their musical activities. I've had students who were doing a school project on a particular country ask to learn pieces from that country so they could perform them to their class - what a fabulous idea! It can be hard to be entirely happy and fulfilled in your music-making if one of the pieces of the jigsaw is missing. It's not impossible, but it's more of a struggle. Whenever I sit in an exam waiting room, with my students, their parents, their accompanist and the exam stewards, or whenever I look at these photos of lots of flute players together, it reminds me of that musical 'village' and how well it works when it all pulls together. The world of music is full of attempts to get the ‘right answer’. Just thinking about flute playing…

What’s the right way to play Bach on the flute? What’s the best make of flute? How do I play high notes quietly? What angle should I hold my flute at? Where do I put my thumb? How should I breathe? I belong to a few Facebook groups and online forums, and whenever anyone asks a question about any aspect of flute playing, strong opinions are expressed. You should definitely do it like this, hold it like this, blow like this. This make of flute is the best. People go to teachers or to masterclasses and are told to do things a certain way, and do their best to follow the instructions, and don’t understand why it’s not working for them. You buy a tutor book and it says “you must do it like this” and “you should not be doing this” (with my linguistics head on, the language of tutor books fascinates me - there's another research project in there bursting to get out one day). I am generalising here of course, for there are voices out there saying “try this”. “This works for me, so you could try it, but also you could try these different ways”. “Go and try lots of different flutes and see which one feels best to you”. Experiment. Some people go to one teacher and take what they say as gospel and never question it. Some people read everything they can on the subject, go to workshops and masterclasses and hear about many different ways to do the same thing. This can be overwhelming and confusing – who are we supposed to believe? Or it can be a springboard for experimentation, finding out what works best for you. I’ve worked on flute playing in detail with quite a number of teachers, from extended periods of lessons to one-off masterclasses or courses, so I’ve come across quite a variety of views on the way to do things. None of them, I would say, have been wrong, but some have worked better for me than others. I look at my own students and I see such variety. As a flute teacher, you spend a lot of time looking at people’s lips and hands, and there are incredible differences (thumbs, in particular, fascinate me – so many different lengths and angles they’ll bend at!). I see my job less as telling people the ‘right answer’ and more as giving them as many possible ways to try as I can. I can show you how I hold my flute with my short thumbs and my hypermobile fingers, but that won’t necessarily work for you if you have long thumbs and your fingers bend a different way. I can help you try different ways of holding it and see what’s happening with your hands when you can’t because they’re stuck out to the side of you. I can suggest a range of different ways to ‘blow’ or to position your lips, so you can try them out and see which one sounds best for you. And I understand the tendency to want to sound like someone else, flute players you admire whose sound you love, but you are you, and even doing exactly what they do (if that was possible) is unlikely to make you sound exactly like them. Your sound is made up of your physical attributes, your particular technique, your flute - and that's a good thing. If you like something about someone else's sound - the richness, for example - then play around to find out what brings about richness in your own tone. There's no 'secret' that anyone can tell you that will magically make you sound the way you want to sound. By extension, that means me reading about different approaches to playing, going to events to find out what other people are doing, and learning new things myself. For me, it also means helping flute players have access to other players and teachers, because with all the will in the world I can’t know everything or be able to demonstrate or explain everything. It’s one of the reasons why I arrange flute days. I run workshops and concerts for my students and flute choir members (pictured above just a few days ago), get-togethers where people can play in a big group, meet other players and share ideas (next one in August), and ones where I invite people with expertise in particular areas to share that with us. The next one of those is with Dr Jessica Quiñones in October – Jessica has listened to my rants, er, impassioned speeches, about the tendency to seek ‘right answers’ and has designed a day where we can “explore and experiment with a variety of methods” of approaching different aspects of flute technique. It’s so valuable to be able to take ideas from different people and try them out for yourself. It's good to meet other players and hear about their struggles with the same issues, and the things that have worked (or not) for them. To see what they do and how they sound. A lot is said in music education about ‘independent learning’ – equipping students with the skills to plan their own development and practice – and I think that’s also as much about learning to experiment with and assess other approaches, to ‘pick and mix’ and find your own way.  My current favourite clarinet study - don't believe the title! My current favourite clarinet study - don't believe the title! A phrase (or concept) that comes up in various forms when talking to and about adult learners is that "life gets in the way". Looking at discourses around family in the data for my MA research highlighted a recurring theme around family and work responsibilities restricting how much learners could play, practise or participate in musical activities. Almost half of the teachers I surveyed also mentioned that adult learners' other commitments had an impact on their learning - whether it was time to practise, having to cancel/ reschedule lessons, or just having the 'head space' to concentrate on learning. According to one study, the ideal teacher has “an understanding of the… responsibilities handled by adults, along with a steady insistence that students be challenged” (Roulston et al., 2015) This is definitely a challenge for teachers - judging how much to 'push' when there are other things going on in people's lives. It doesn't only apply to adult learners either. With children we're also balancing it up against other activities, school work, family circumstances, sometimes ongoing medical conditions. There's also working out how much of a priority music is for that individual person - the bigger a role it plays in their life, the more 'challenge' they're willing to take on to develop their skills. But the level of challenge can be both under- and over-estimated, and another of our jobs as teachers is to help students be realistic about that. Existing research highlights adult learners’ high levels of intrinsic motivation (Lamont, 2011, Taylor, 2011) - learning because they want to - but also finds that many struggle with 'unrealistic expectations' and subsequent frustration with their progress. We need to find ways of showing that it is possible to make progress as an adult, but it's not always going to be easy. And there isn't a set 'path' - some people spend weeks trying to get a reasonably clear sound on a flute; others quickly find a nice tone, but take longer to find the right hand position for them to balance the instrument well. Some people easily settle into a pattern of practising every day (one of my adult students works from home and has quick 'flute breaks' throughout the day), whilst others find it harder to fit another activity into their lives. (This has got me wondering about how music learners - both adults and children - manage increasing practice time and what impact that has on their progress, but I think I'll leave that for a future post). So part of the challenge is finding time, and again, how much of a priority music is has an impact on that. Now, I'm not being disparaging about those people for whom music isn't such a priority, or about different reasons for making it a priority - whether that's because they want to 'take it seriously', or because they really enjoy it, or because it's their 'me time' or their ten minutes of fun - I'm not going to judge the validity of anyone's reasons for playing music. My own journey of learning the clarinet - which has given me great insights into what it's like to be a beginner again - has brought up the issue of priorities for me too. I had set myself a challenge to do 100 sessions of clarinet practice in the last twenty weeks. It started well, I had a lovely chart where I coloured in boxes each time I practised, and for the first month or so I was on track. But then I got more students (always lovely - but slightly mystified by a sudden rush of enquiries in October!), I had some concerts to play in, I had the small matter of putting together a PhD proposal. The clarinet practice declined. And then I got a cold, and playing the clarinet with a cold is disgusting. I can cope with playing the flute with a cold, a cough, blocked ears - it's not fun but it's manageable (and I kind of have to sometimes, it's my job!). I don't have to play the clarinet though, so I didn't. I salute you reed players who manage to carry on when your head is all stuffed up. So I got out of the habit a bit. I've got back into it over the last few weeks, but there have been Christmas gigs and other festivities going on too. So I haven't done 100 practices - I can't actually tell you how many I have done as I have to admit I abandoned the chart (it was so colourful too!). The thing is, when I picked it up again, I realised I do enjoy playing the clarinet. It's a different sound, feeling and range to the flute - ahh, lovely low notes - and it's a different challenge as I'm still learning the basics and building up stamina (which I lost rather a lot of and am having to gradually get back). I'm enjoying finding out about the similarities and the differences to flute playing. But it isn't top priority - musically, the flute will always be that for me. And when life gets busy, the things that aren't top priority will drop off for a while. I don't always do as much flute practice as I'd really like - there are only so many hours in the day after teaching, admin, research, writing etc - so I have to prioritise what needs to be done, such as pieces for upcoming concerts (and sometimes that's very concentrated practice on the 'tricky bits' in short bursts). So I understand where students are coming from if I get to their lesson and they tell me they've not done much practice this week - I really do. But I will suggest ways of making practice more effective, and remind them that really, five minutes a day IS better than nothing, and five minutes a day is also better than an hour once a week. Life does get in the way, sometimes completely, and that's - well, that's life! But if you enjoy playing your instrument (even if the idea of practising is sometimes... urgh), then it's absolutely fine, in fact it's very good for you, to prioritise those bits of time doing something you enjoy. I need to remind myself of that sometimes too! -----------

Lamont, A. (2011). The beat goes on: music education, identity and lifelong learning. Music Education Research, 13(4), 369-388. Roulston, K., Jutras, P., & Kim, S.J. (2015). Adult perspectives of learning musical instruments. International Journal of Music Education, 33(3), 325-335. Taylor, A. (2011). Older amateur keyboard players learning for self-fulfilment. Psychology of Music, 39(3), 345-363.  Last week I wore a variety of hats - not in a metaphorical sense, but in a real one. There was the mortar board at my MA graduation - a lovely, if rather blustery day celebrating the end of the course and catching up with some of my fellow distance learning students/ survivors! Then there were the Santa hats. (Yes, hats, plural - I have acquired quite a few of them, mainly for flute choir purposes, including some glittery ones and ones with flashing pompoms! So I thought I'd wear a variety of styles...). Firstly the end of term for the baby and toddler music classes I teach at Rhythm Time, where I (and the babies) dressed up in our festive best and had lots of fun with bells! Then at the weekend Sheffield Flute Choir had an outing to play at Weston Park Museum. Twelve (of our total membership of around thirty) flute players all in Christmassy head gear serenaded museum visitors - and the queue for Santa's Grotto - in the fabulous surroundings of the About Art Gallery. Finally, I've been wearing a very cosy bobble hat, a Christmas present from a student last year - which has been much appreciated in the windy wintery weather as I go about between lessons! In the midst of all this hat-wearing, I've been helping students out with pieces for Christmas concerts and handing out exam certificates (well done all of you for so much hard work this term!). It's the end of a year (almost) and graduation felt a bit like the end of an era but I'm so looking forward to what next year has to bring. ------ ps to read a fabulous blog from a lady who wears many (metaphorical) hats, plays the flute and is doing a really interesting PhD project, and who I had the pleasure of meeting at the SEMPRE study day earlier this year, pop over to https://diljeetbhachu.wordpress.com/about |

Keep in touch

I have an email newsletter where I share my latest blog posts, news from the flute and wider musical world, my current projects, and things I've found that I think are interesting and useful and would love to share with you. Expect lots about music and education, plus the occasional dip into research, language, freelance life, gardening and other nice things. Sign up below! Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed