|

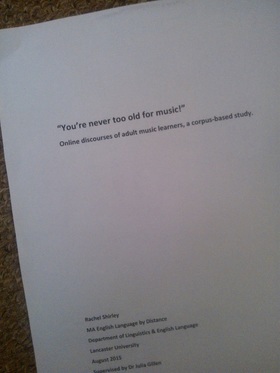

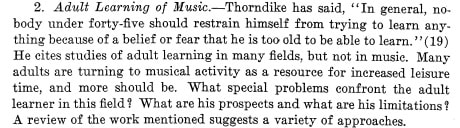

The other day, I came across this article from 1938 entitled 'Needed Research in Music Education'. Leaving aside the "nobody under forty-five" bit (lets just make that "nobody"!), it's another to add to my collection of quotes which basically say "someone should be researching adult learning in music". They pop up in the literature every few years, whilst actual research into adult learning appears at a slow trickle. They're one of the things that keep me going with my research, when the thought of the long, slow process seems overwhelming.

Articles about adults learning music appear in the more mainstream press now and then too - why it's good for our (ageing) brains, the story of someone deciding to take up the piano after dreaming of playing for years. I was pleased to spot a magazine article this week about the benefits of learning music as an adult, but then rapidly disappointed by lines about "demoralising (or just plain boring) school lessons" and "shake off the shackles of childhood piano lessons and start having fun". There's nothing necessarily wrong with teaching yourself or making use of YouTube videos, as the article suggests, but this disparaging view of music teaching got my back up. Yes, there are boring/ miserable lessons/ teachers, but there are so many teachers that I know who are trying their best to make learning music enjoyable and engaging for all ages. Although the article pushes the social benefits of music, it takes confidence to go and join a group - I'm not sure how easy some people will find it to step out from behind their computer and go out to play in public. That can be something that a teacher can help to 'hold your hand' through, playing with you in lessons, arranging informal opportunities for you to play with and in front of other people, suggesting suitable ensembles to try out. Going along to lessons is a social interaction in itself, and don't we spend enough time in front of a screen as it is?! I have a couple of other issues with dependence on video lessons - firstly, there isn't someone there observing you and helping you out. I've come across adult learners who've struggled with teaching themselves through online courses, because they're trying to follow a set of 'one size fits all' instructions. The instrument hasn't been set up properly for their particular body shape and size, their hand position is all wrong for the length of their fingers, and they're wondering why it doesn't sound right, and even more worryingly, it feels uncomfortable. Look at just a few clips of professional flute players and you'll see variations in how they use their hands, arms, mouths - because bodies aren't all made the same! This is something that a teacher can help to work out, helping you to avoid injuring yourself at the same time (it might seem difficult to injure yourself with an instrument but the damage that musicians do to their bodies is a big issue - if you're doing a repetitive movement many times, you want to be doing it in the best way possible). They're also there to help with the mental and emotional aspects of learning - supporting you through the frustrating times and helping you navigate the process of learning music alongside all the other challenges in life. I entirely understand that it costs more to take lessons than to watch YouTube for nothing (and clearly I have a vested interest in people taking lessons!), but I wonder whether sometimes 'free' isn't the bargain it seems to be. My other issue is an apparent obsession with speed (of learning, not of playing!) - online teaching resources I've seen use phrases like "fast-track your results". One, specifically for adults, promises to "skip the simplistic and slow approaches used with children and will get you playing in no time". While I'm not doubting - and research, including my own, suggests - that adults need some different approaches to children, I am wondering what's so wrong with 'simplistic and slow'? I certainly see a desire for quick results in many students (as much in children as adults, I would say), but surely there is nothing wrong with taking your time? As well as getting away from the screen, why can't learning music also be a change in pace from the rest of life? I'm reminded of the 'slow food' movement which celebrates traditional methods of growing and cooking, and of the trend for mindfulness which encourages people to slow down and observe. Why should learning music be a race? Why shouldn't we enjoy the gradual process, and celebrate the beauty of playing something simple well. Perhaps adults do want quick results. Maybe they don't want teachers (although my research suggest that that plenty of them do, and that the teacher-student relationship is really important). I suspect that what really works well for most learners, whatever their age, is a combination of approaches - individual lessons, playing with groups, making use of some online resources, experimenting on their own. We need to look at what benefits learners most - musically, but also mentally and physically - is it the quick fix that seems initially most appealing, or is it taking your time and immersing yourself in the long, wonderful process of learning? We could say that 'slow and steady wins the race' but I think what's most important is that it isn't a race!

0 Comments

'Getting everything done' is a common issue in my life - trying to balance playing, teaching, all the admin that goes with those, doing research, all the usual things that you have to get done in life and actually 'having a life' isn't always easy. I see it in my students too. It's proving to be a frequent theme in my research (and anecdotally) with adult learners - how do you find time to practise an instrument, learn music theory, read about the history of your pieces etc, whilst also doing a full-time job, bringing up children, and going to the gym regularly (or whatever it is that fills your weeks)? I increasingly see it with younger students too - how do you fit in learning music, all that homework, competing with your sports team and all those birthday parties, and still have some time to hang out and do nothing as well? When you're younger, you probably don't think in terms of 'productivity'. As an adult these days, the word is everywhere. We're meant to be getting loads done (whilst simultaneously taking plenty of time out for self-care). There's a massive industry around teaching people ways of doing more in less time, books packed full of methods to help you be more productive - if only we could find time to read them all! I was pleased to be chosen as part of the pre-launch reading group for Prof Mark Reed's new book The Productive Researcher - it's great to be supporting someone who's self-publishing their work, and I was hoping to find ways to make the most of my time. I wasn't sure at all what to expect, and worried slightly that it would be full of what felt like unachievable methods for 'doing more', just tailored towards academics. What I actually got was not at all your usual ‘how to do more’ book. Mark writes in an open, friendly way, sharing his own experiences of discovering how to be productive, but also happy in your work. There’s clear academic research behind it – in looking at other people’s theories and approaches to productivity – but it reads like the words of a supportive, gently challenging mentor. You can read this book quickly and pick up useful ideas from it, but I think to get the best from it you need to spend some time and mental energy to work through the questions and exercises, and commit to trying to use the principles. It’s not (nor does it promise to be) a quick fix, but it really gets to grips with what lies behind our struggles with ‘being productive’. The first part of the book proposes that to be productive in our work, we need to know why we’re doing the work, and asks us to pin down our motivations – I particularly liked the idea of having back-up motivations for the times when our main ones falter. There’s a re-framing of SMART goals as “Stretching, Motivational, Authentic, Regardful and Tailored” which I felt was much more motivating than the original concept. The second part describes ways of putting these motivations and goals into action. There’s a focus on prioritising and using your time well – that the way to feel/ be more productive is to spend less time on the things that don’t contribute to your overall goals. I loved the idea of firing up your day with enjoyable work first, rather than saving the bits you like as a reward for getting through the less fun stuff. There are practical tips on managing the time you spend in meetings, on social media, and dealing with the never-ending stream of emails! I can imagine that some of these would take a fair amount of willpower to implement in the pressured atmosphere that academics are working under, and there are bigger issues at play around what is expected of researchers, but some of these steps would definitely help gain back some sense of control to your working life. Although it's aimed at researchers, meaning that some of the scenarios are academia-specific, e.g. submitting papers to journals, examining a PhD thesis, there's a lot in this book for anyone who wants to feel like they're making the most of their days. Being really clear about your motivations and priorities, and learning not just how to say 'no' but how to decide what to say 'no' to, are lessons that anyone could find useful. Yes, there are days when whatever procrastination activity you like to indulge in seem far more appealing than practising your scales or going for a run in the rain, but if you're clear about your overall motivation and what's important to you (you want to be able to join a band and sight-read new pieces at rehearsals, or you want to complete a half-marathon) you can keep revisiting that to keep you going and enjoying what you do. Bloggy disclaimer things: I received a free copy of the ebook version of The Productive Researcher and was asked to write an honest Amazon review (which I did - it's basically a reduced version of this blog post). The links above are my Amazon affiliate links which mean that if you buy the book through those I will receive a small amount of commission.

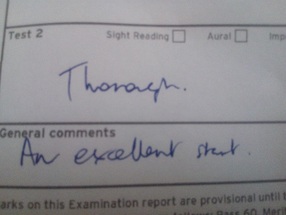

One size doesn't fit all - gigantic wind band fleece! One size doesn't fit all - gigantic wind band fleece! In my last post, I talked about the value of taking different approaches to playing musical instruments, and trying them out to find the best ones for you. In a way, the tendency to try to find 'one size that fits all' is one of the things that led me to want to research adult music learners. It was the attitude that I'd sometimes come across that "adult learners are... X". One of the first results that came up when I searched online was a quote from a music teacher saying that "adults are notoriously difficult to teach". My own experience suggested that wasn't necessarily the case, but it did start me wondering about whether adults learning did have many common characteristics, or whether they were really quite diverse (my 'work in progress' answer to that, from my research so far, and from teaching increasing numbers of adults, is probably 'both'!). My reading of adult learning literature is bringing up issues around what exactly that constitutes - the research I've looked at so far tends to focus on 'basic skills' education or, to a lesser extent, retraining, which is quite a different sort of experience to learning an instrument, although clearly there will be overlaps in the basic issues around 'learning'. But it has got me thinking about where music education sits in all this - there are plenty of debates around how important it should be considered in schools, but what actually is music education for adults? Certainly it's rare, though not impossible, for someone to take up an instrument in later life and become a professional musician - setting aside for now how we define a 'professional musician' because that's a whole other can of worms! - so it's not, generally, 'retraining' for a new career. Is it a hobby, or leisure activity? It does feel somehow different from hobbies where you perhaps attend a term of evening classes, or go along once a week to a club (and I always feel the word 'hobby' has a sense of casual interest, which doesn't quite fit how some adults treat their music - or indeed other non-work activities). I do think that music teachers need to take account of those different attitudes - what someone needs from lessons varies depending on what they want out of them. Some adults seem to start with a clear idea of what they're aiming for, whilst others don't so much, and that's also part of our job, to support them in finding out what that is and as it might change along the way (or maybe never quite finding out exactly, but enjoying the process). Some of my Masters research found adult students being pressured down the exam route by teachers, and maybe that's an example of trying to use the same approach for everyone. I've also read some discussion this week about how long it should take learners to reach certain stages on an instrument, and I think that's definitely a topic for a future 'one size fits all' post, which seem to be turning into an accidental series. More soon!  April has arrived in a stereotypical display of sunshine and showers, and I've had a sudden burst of spring cleaning enthusiasm. In the course of tidying some paperwork (I've not yet found the courage to tackle the sheet music mountain), I came across the print-out from my school 'careers interview' where I somewhat confused the careers guidance person by reeling off a very detailed plan about how I wanted to be a musician and how I was going to go about it. I was single-minded then, but I'd been through phases of wanting to be various other things - a writer, a translator, something to do with nature or biology. When I went off to University to study music, I found that single-mindedness going off track a bit. I discovered I was still really interested in language. I started reading about psychology and philosophy and found those fascinating too. Whilst berating myself a bit for not being able to 'stick to one thing' I ended up a few years down the line with both a University music qualification and an Open University degree made up of (hang on, let me think) Latin, Greek, general humanities modules (I loved the mixture of subjects these let you explore), philosophy, psychology, English literature and linguistics. I studied linguistics for my Masters because I was absolutely hooked on discovering the ways that analysing language could enlighten all sorts of subjects. I sometimes felt a bit apologetic though, especially when people gave me slightly puzzled looks - why was I not doing a music Masters? Why was I on this course where 90% of the other students were English teachers? But I used linguistic analysis techniques to kick off my research into adult music learners, and in the process found myself heading down the route of interdisciplinarity (nice description of what academic interdisclipinarity is all about here). Quite an exciting route as it turns out! It becomes really obvious when I'm looking at conferences to attend. I look at all the music education conferences (and those that are about music psychology and music in general). Then at the linguistics ones, and there are a lot of those - not all relevant, but anything in sociolinguistics, corpus linguistics or discourse analysis catches my eye. But then I'm also interested in education in general, and adult education in particular, which opens up a whole other array of events. So far I've presented posters at the Manchester Forum in Linguistics and the SEMPRE (music psychology and education) Postgraduate Study Day. I'm very excited to have been accepted to give spoken presentations at the International Society for Music Education (ISME) research seminar this summer, and at the European Society for Research on the Education of Adults (ESREA) triennial research conference in Ireland later in the year. It's a little bit overwhelming to have all these options, but mainly it's wonderful to be able to draw on all these different areas and hear about the research and experiences of people researching such a mixture of topics. It's interesting that Universities have had to give a particular name to research that crosses subject boundaries, since those boundaries have never been entirely clear-cut. Life doesn't sit well into perfectly defined 'subjects' - it overlaps. A conversation you have in the gym might spark something that helps you approach your flute playing in a different way. An experience of playing music might feed into another area of your life. The lines between physical and mental health aren't as defined as we once might have thought they were. But perhaps being able to give this boundary-crossing a label - 'interdisciplinary' - has helped me feel more at ease and happier with my tendency to explore lots of different areas and not just focus on one. I'm not sure I can ever imagine only 'doing' or 'being' one thing - a teacher, an academic, or anything else! Now, about that sheet music mountain...  I've just been listening to this programme from BBC Radio 4 - School of Thought: Late Learners. Presented by former Conservative MP and universities minister, David Willetts, it's the last of a series looking at education at different stages of life. I haven't listened to the earlier programmes yet, but on this one on adult learners obviously caught my eye (ear?!). He argues for a more flexible education system which takes account of the fact that "life is messy" and makes it easier for people to return to education as adults - the focus is on higher education, so he's suggesting things like better funding schemes and being able to transfer credits for courses studied at different institutions. Although private music lessons are a bit different to a university course, some similar barriers apply to adult learners. Financially, it's easier (though my no means guaranteed) to find help with learning music when you're younger - some instrument hire schemes are only available to people below a certain age, there are more charities to apply to for help with tuition, summer schools or buying instruments (I had support from several organisations as a child - towards buying an instrument and attending orchestra courses/ tours). It's very rare (impossible?) to find help like this for adult learners. Some schools have free/ subsidised music lessons for children from lower income families, there is some wonderful music work being done for young people who might not otherwise have access to it, but what does an adult with not much money do if they want to learn an instrument? There are also fewer opportunities to play when you're no longer in school - some of my students can join their school band after a term or two of lessons, but it's much harder to find groups that will take adult beginners. There's no end of term concert if you're not a school kid (one of the reasons I started putting on informal concerts for my students - of all ages - to take part in). If you're interested in entering competitions - something I've heard a lot of discussion about with budding composers in particular - there are often age limits on these. So whether you stopped playing your instrument after school and came back to it, didn't have an opportunity to learn as a child, or suddenly woke up one morning at the age of 46 and decided you wanted to play the flugelhorn, there are definitely some barriers (as well as the ones that adult life itself puts there, as in my previous post). Apart from being a little disappointed by the implication that adult learning is something you do to 'make up' for missing out on education earlier (e.g. dropping out of school), I thought there were some really strong points in this programme, in particular the discussion of the wider benefits of more people gaining more education, beyond the more obvious outcomes of getting a better/ different job. It was also fantastic to hear from a neuroscientist that our brains are just as capable of learning as adults - the previous thinking that childhood/ teens were the peak learning age has been challenged by more recent research - so any feeling that it's 'harder to learn' at an older age may just be down to preconceptions. (Mr Messy image from http://www.themistermen.co.uk/mr_men/mr_messy.html)  Last week I wore a variety of hats - not in a metaphorical sense, but in a real one. There was the mortar board at my MA graduation - a lovely, if rather blustery day celebrating the end of the course and catching up with some of my fellow distance learning students/ survivors! Then there were the Santa hats. (Yes, hats, plural - I have acquired quite a few of them, mainly for flute choir purposes, including some glittery ones and ones with flashing pompoms! So I thought I'd wear a variety of styles...). Firstly the end of term for the baby and toddler music classes I teach at Rhythm Time, where I (and the babies) dressed up in our festive best and had lots of fun with bells! Then at the weekend Sheffield Flute Choir had an outing to play at Weston Park Museum. Twelve (of our total membership of around thirty) flute players all in Christmassy head gear serenaded museum visitors - and the queue for Santa's Grotto - in the fabulous surroundings of the About Art Gallery. Finally, I've been wearing a very cosy bobble hat, a Christmas present from a student last year - which has been much appreciated in the windy wintery weather as I go about between lessons! In the midst of all this hat-wearing, I've been helping students out with pieces for Christmas concerts and handing out exam certificates (well done all of you for so much hard work this term!). It's the end of a year (almost) and graduation felt a bit like the end of an era but I'm so looking forward to what next year has to bring. ------ ps to read a fabulous blog from a lady who wears many (metaphorical) hats, plays the flute and is doing a really interesting PhD project, and who I had the pleasure of meeting at the SEMPRE study day earlier this year, pop over to https://diljeetbhachu.wordpress.com/about  It seems a bit rude starting a blog post with 'shut up'. Don't worry though, this isn't me telling you to do any such thing... unless you want to! In the midst of my Masters, I discovered 'Shut Up and Write Tuesdays' - an online writing group, aimed at academics, which has the simple premise that, for one hour on a Tuesday, you sit down and get on with a piece of writing that you're working on. There are different hours depending on where in the world you are (and if you're feeling particularly in need of writing time you can join in with more than one) and wonderful support from dedicated Twitter accounts which tell you when it's time to 'shut up' and generally cheer on the participants. I found this incredibly helpful when writing my dissertation, especially when it seemed overwhelming. I didn't initially think I could get much done in an hour, but these sessions really helped me to understand the value of short blocks of time. I've also used them to write blog posts! A comment on my previous post (thanks Katherine!) mentioned the same idea around training for sports and practising instruments - often people feel there is no point in going for a short run or squeezing in a short practice, but these small blocks can be surprisingly productive. Something generally is better than nothing, and often a short block can feel a lot less intimidating than thinking you must spend hours on a task. I've found it often works as a kick-start to more work - I think "I'll just do this hour of writing" and find it fires my enthusiasm so much I'm still going several hours later (with appropriate breaks of course, SUWT is a big supporter of cups of tea!). Or it helps me 'break the back' of something I've been putting off because it feels like a huge task, so I feel happier to come back to it later - whether that's a first play through of a new piece of music, or like today, where I got the basics of my first conference poster in place. Having never put together a poster before, I had a definite sense of not knowing where to start, but sitting down for that hour thinking "I'll just do something to get it started" has made it feel much more manageable (rather than it just sitting on my to-do list, glaring at me). Short blocks are also working well for my clarinet practising challenge - just ten minutes regularly (often during breaks from admin and writing - I keep my clarinet near my desk) are definitely making a difference. That might not exactly count as 'shutting up', especially if you heard some of my higher notes... It's very easy to put off writing, or running, or practising, or all sorts of other tasks, because you think they're going to be monstrous, and it's also very easy to come up with reasons (some might say 'excuses') not to do them. But sometimes, you do need to tell yourself to 'shut up' - actually getting on with it is amazingly effective at silencing all those thoughts about how terrible it's going to be! Talking of monsters - the posters I'm preparing are based on the section of my dissertation which examines discourses around adult learners and their teachers - featuring the lovely quote from one learner that their teacher is "not an ogre". I'm looking forward to presenting it at the Manchester Forum in Linguistics and the SEMPRE Study day on Music Psychology and Education later this year. Is there a task you could do with 'shutting up' and getting on with? Image from https://openclipart.org/detail/219746/keep-quiet-sign In my last post I hinted at some of the similarities between learning an instrument and training for a sport, and since I've just come back from my induction at a new gym, it seems like a good time to explore that a bit more. In some ways music and sport seem worlds apart - maybe music is seen as more of an 'intellectual' activity against sport's physicality. I know when I was at school I was 'rubbish' at P.E. and was definitely put in the box of being good with my brain rather than my muscles. The funny thing was, outside of school I took dance classes for years, and whilst I wasn't brilliant at that, I got to a decent standard - I reached the point of dancing on pointe in ballet and won a few medals in Highland Dancing competitions. So why was I no good at basketball and hockey but alright at dancing? Partly I think that comes down to one of the similarities between music and sport - that mental attitude is a big part of doing well. I wanted to dance, so I worked at it. I've no doubt that the fact it was movement to music helped. I had teachers who were encouraging, who paid a lot of attention to each student's physical make-up and explained to them what particular aspects they would need to do more work on to succeed. There were exercises to work on at home between classes (although I fully admit to getting lazy with them in my teenage years!) which meant that there was more progress than if you just turned up once a week. In other words, very much like practising an instrument! In my MA research I discovered discourses of 'learning music as training' in terms of taking small steps, having goals and aims, tapering your practice before an exam. I also came across terms which flagged up discussions around mental preparation techniques often used in sports training, such as visualisation - where an athlete might visualise how they'll run that race, a musician could use the same technique for a performance. Learners described exams as hurdles and like a treadmill, suggesting a need to mentally push past barriers.

However, the similarities between sport and music aren't just in psychological approaches. Making music is a physical activity. Playing the flute doesn't (normally) involve any running or big jumps, but it does require the movement of many many muscles - in your face, your tongue, your fingers, for breathing and blowing. You need to hold something up with your arms for prolonged periods of time. It ideally needs good posture and a strong 'core' (I've found that Pilates is wonderful for that). But from thinking of myself as not a 'sporty' person, it took me a long time to realise just how physical playing an instrument is. In the text I analysed for my dissertation I found learners talking about building up strength and about the best thing to eat before performances or exams, and I was pleased to see this awareness of the physicality of it. It's certainly something I try to explain in my lessons - that learning to play is partly about building up strength and flexibility in new muscles. Students (especially adults) who've done a sport often find these comparisons helpful - if someone has trained for a marathon, they understand the idea that you need to build up from short runs. It takes time, but if something feels difficult now, it can be worked on, steadily and gradually and it will get easier. I suppose this may be one of the reasons why adult learners feel they can't make as much progress as younger students, that age is physically 'against them' - something I want to look into a bit more, to find out whether research shows that really is the case or whether it's more assumptions about what they 'can and can't do' that hold people back. This need for 'work' ties in with one more similarity between sport and music - the idea of talent. I do think that some people find it 'naturally' easier to do particular activities - that might be because of their natural physical build or because of previous experiences that mean they have strength in particular muscles, or have developed particular parts of the brain. However, talent will only get you so far without willing and work. Someone who really wants to do something, and is prepared to put in the time and effort, is going to get far further than someone who has a physical 'advantage' but doesn't practise. This video from SportScotland (which I've posted before) makes this point really well. I can really feel the difference in my playing when I'm physically fitter, one of the reasons that the start of this term sees me back at the gym. To read more from some inspiring musicians about their take on flutes and fitness, have a look at Music Strong and the Flying Flutistas!  Yesterday, I submitted my MA dissertation online. Today the hard copy is being bound and tomorrow I'll post that off to the department. So I've reached the end... sort of. Although I've no more work to do on the Masters, I will be waiting (slightly anxiously, as mentioned previously, I'm not good at waiting for results!) until October for the final mark. Then graduation is in December so after that it's definitely, really finished! The last few weeks of bringing it all together have been stressful, but also hugely enjoyable to see it take its final shape. Despite times when I thought it would never turn into anything resembling a dissertation, I've found the whole process incredibly fulfilling. I have to say a big thank you to my wonderful supervisor, Dr Julia Gillen, for her guidance, enthusiasm for the project, listening to me rambling on (when you're a distance learning students the odd occasions when you actually get to visit your University and talk about your research are terribly exciting!*) and for giving me the confidence that I could actually do this thing! It does feel very strange to be at the end - I've done the course part-time over three years and the dissertation has been slowly growing from an embryo of an idea early last year, so it has occupied my brain for quite a long time! I don't, however, feel like I'm finished with the research yet. The final product only used about half of my original plan - who'd have thought that a 12,500 word limit actually isn't that much! So while I did look at how adult learners talk about being 'older' and how that affects their learning, and what they say about music exams, music teachers and their families' involvement/ impact on music learning, there are whole areas which I started looking at but couldn't cover in detail - how they talk about being 'musicians' or not, whether there are any patterns in how they use modality (e.g. will vs might), what other grammatical patterns there are and what these might imply. I've covered how emotions are portrayed around exams and teachers, but there is so much more to say about that, including looking at how emoticons are used in the online text to portray moods and emotional reactions. I'd like to look at text written by teachers about adult learners and see how that compares under the same sort of analyses - what discourses are evident in that and are they the same as the ones that came out of my corpus of text written by adult learners themselves? (I suspect they won't match up completely - I certainly found from my survey that teachers talked about 'skills' needed to teach adults, whereas in the corpus adults described the 'qualities' of their teachers). I'm interested to find out how different the concerns of adult learners are to younger learners. I wan't to know what it is that makes some adults more motivated, or more independent at learning - are there any connections with their previous musical experiences (learning as a child or not, etc), or the style of music they're learning? Are there different discourses of adult music learners in different cultures or countries? Is this starting to sound like a lifetime's work to follow up all these loose ends? I suspect it is! For now though, while the research is all still very fresh in my mind, I'm looking at trying to take some of my research out there into the big wide world - as a poster or presentation at conferences, hopefully at some point as an article somewhere. I will be putting it online once it's marked, and discussing my findings a bit more on here too. I'd like it to reach the people it actually makes a difference to - adult learners themselves, teachers and the people who train teachers - so will be thinking about how to share it with them too. And since I now have a little bit more spare time, I'll be setting myself a few new musical goals... watch this space! (*I would also like to thank all the other people who have patiently listened to me rambling on about it over the last year, whether they were really interested or not. You know who you are!)  It's the start of the school summer holidays here, with lots of students and teachers taking a well-deserved break. I'm having a couple of weeks off from teaching but much of that time will be devoted to finishing my MA dissertation which is due in mid-August. I'm currently finishing writing up the section on how adult learners write about exams (well, I have been this morning - I'm currently having a short break, a cup of tea and a packet Hula Hoops, and writing this blog post!). My research has revealed some striking metaphorical language used about the experience of preparing for and taking exams. Perhaps not surprisingly, there's a lot of negative terms with groups of words which suggest violence - executed, hanging, murdering, killing - and pain - excruciating, suffering. The process of entering, preparing for, and taking exams is compared to a military campaign with terms such as withdraw, forearmed, territory, officer, bullet, target, medal - and there are also hints of a treacherous naval expedition - uncharted, adrift, wreck. But thankfully we also see the horizon and there is talk of surviving. There are also discourses which suggest that exam preparation is like training for a sport - hurdle, treadmill and discussion of tapering, and even what to eat on the day (which explains the initially mystifying appearance of potato in the corpus)! There are lots of terms which relate to movement - exams approach, near and loom. There is pushing and pulling, but also swinging and waltzing, and quite a bit of wobbling like a jelly. Adult learners express concerns about facing 'scary' examiners, but tend to find in reality that they are kind, gentle, courteous, calm, supportive, encouraging. 'Support' is a common theme, surfacing in descriptions of how teachers help learners prepare for exams and boost their confidence - my teacher is an angel, my teacher is lovely and encouraging. They also mention how helpful it is to have a friendly accompanist, if you play an instrument which is supported by a piano part. Online communities also offer support, with adult learners offering sympathy and hugs during the build-up and the wait for results, and many congratulations (for successful results, but also for being brave enough to take the exam in the first place!). A couple of months ago, I posted about my own plans to sit two Grade 1 exams, learning the clarinet more or less from scratch, and taking my piano playing right back to basics. I took both of these exams a couple of weeks ago. It was an incredibly useful experience as a teacher to be back in uncharted territory - although I've taken many flute exams, I'd never sat one on another instrument, so it did feel rather like being a beginner, not quite knowing what to expect or exactly how well I needed to play at this level. Nerves definitely kicked in, and I had no idea how my playing of each instrument would respond under pressure (whereas with the flute, I have a pretty good idea what happens and how to deal with it). It turns out that the fact my mouth dries up with nerves is even more 'bleurgh' with a reed in my mouth, but it is manageable! My experience of the examiners definitely agrees with those that the learners in my study talk about - both were friendly and welcoming. The one for my clarinet exam had no idea I had any musical background, so I felt I was being treated as she would any adult beginner, and it was a very positive experience, topped off by a lovely comment on my mark form declaring the exam "an excellent start" on my clarinet journey. What a boost that would be to any beginner! The piano exam was a slightly different experience, as I was sitting another exam (Flute Performance DipLCM) on the same day, with the same examiner! So she was aware that I had experience of music and exams behind me, and indeed joked that the supporting tests at Grade 1 should be fairly easy for me! ;) All the same, I still felt that I was judged on my performance as a Grade 1 piano student, rather than there being any 'extra' expectations of me (and I know that adult learners often feel they are expected to do 'better' to pass exams than children, simply because they are older). This was really helpful for me, as part of the whole point of sitting this one was to help build my confidence on the piano, to learn it properly rather than feel like I 'should' be at a certain standard with it due to the rest of my musical background. Still, I have to admit that getting full marks on the musical knowledge, aural and sightreading certainly did help with my overall score! It also underlined to me as a teacher how much impact these skills can have on how you get on in an exam (as well as being incredibly useful skills when making music, which is why they are tested in exams). For both instruments, I definitely agree with the learners in my study, when they say that having supportive teachers is a huge bonus in the exam process, helping you feel like you are on the right track and you can do this scary thing! I also agree with their thoughts about accompanists - it is incredibly comforting to work with someone you know is 'on your side' (something I found a bit daunting about the piano exam, as you're on your own there!). And yes, I did sit two exams on the same day. As well as the Grade 1s, I had entered myself for a flute performance diploma. I'm pleased to say I passed that too, and even more pleased to say it was an enjoyable experience. More about that in a future post, soon... but I must get back to the dissertation! |

Keep in touch

I have an email newsletter where I share my latest blog posts, news from the flute and wider musical world, my current projects, and things I've found that I think are interesting and useful and would love to share with you. Expect lots about music and education, plus the occasional dip into research, language, freelance life, gardening and other nice things. Sign up below! Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed