|

I've had lots of conversations recently about the qualities that make the sort of musician that other musicians want to work with (for work read any sort of musical activity that you want to take part in, paid or not). Being able to play your instrument goes without saying, but there are other qualities that are just as important. In fact, many people I've spoken to would rather work with someone who demonstrates these qualities and behaviours, above someone who is technically 'better' at their instrument. I've also been reading a lot about letting go of the stereotype of the 'artist' as someone messy, disorganised, unhealthy, self-destructive (see Elizabeth Gilbert's 'The Artist's Way' for interesting discussions on this). For most people, you'll do better work and get more work if you're organised and disciplined, rather than believing that you can 'get away' with not being these things because you're in a creative environment.

I started writing a blog post about these qualities, but it got rather long, so I've turned it into a series instead. Lots of these are things that you don't need to be inherently good at, you basically just need to decide to do them and, well, do them. It might take a bit of practice if you're not used to doing them, but you're a musician, so you know what practice is all about, right? Decide what you want the outcome to be, do the stuff you need to do to reach that outcome, repeat it often until it becomes habit. I'm often told that I'm 'so organised' but I don't think I'm a naturally organised person - it's just that I see the benefits of being organised massively outweighing any advantages to being disorganised! No. 1 - Be on time There's an unwritten rule that if a rehearsal 'starts' at a certain time, you should be there about fifteen minutes before that time, in order to set up and be ready to start playing at the start time. I remember being told about this by a teacher years ago when I went to my first youth orchestra rehearsal. Obviously, travelling can be unpredictable, so if you can aim to be there a bit before that in case of delays, even better - you can always have a wander around outside if you're there before anyone else. I speak from many years of being early for things and having to wander around for ten minutes. If you're always early, and you help to put the chairs out, you get extra musician bonus points (which don't come with any rewards, except the recognition that you are a prompt and helpful person, and hugely appreciated for it). Likewise, if you have a break in rehearsal, be back promptly at the end of it - the social aspect of playing in a group is very important, but if you know you've got fifteen minutes break, then make sure you fit in your cup of tea and your visit to the loo well before you need to be ready to play again, rather than chatting for 14 and a half minutes then rushing around and being late back. If you usually arrive in plenty of time, then people will be far more accepting of the odd occasion when you are late. If you're late every single week, that's annoying and doesn't tend to make people think favourably towards you. There are exceptions to any rule, of course, and once you've been (early) to the first rehearsal you can figure out what happens in each particular group. For example, my flute choir 'starts' at 10am, but the building only opens just before this, so it's a relaxed start to rehearsals - get there as close to 10 as you can, get set up, get started once most people are there (usually about quarter past). It's also fine for people to only come to part of a rehearsal, but that won't work for every group. Get to know what is the norm for your group. If you know in advance that you have an unavoidable appointment, let someone know you'll be getting there later (and check that's OK). If you get held up in traffic, hopefully you'll have someone's number so you can text and let them know. If you genuinely can't get there until right on the start time every week, then it's probably worth mentioning it to the group leader - I reckon most people would rather know that someone is keen but can't get out of work any earlier than think that you're just not enthusiastic enough to get off the sofa in time. The arguments I hear against this are predominantly a) "I'm rubbish at being on time" and b) "but it's supposed to be fun!". If you tend to get distracted and forget what time it is, then end up not leaving on time, set an alarm! The benefits - not being the person that everyone else is rolling their eyes at as you squeeze through to your seat, knocking over music stands on the way, and also being seen as a reliable musician that people want to work with - are well worth it. And yes, music is generally meant to be an enjoyable, satisfying thing to do ('fun' is a tricky word, often suggesting the opposite to working hard and being disciplined, but that's a whole other discussion), but I'd argue that it's more enjoyable if you're not stressing yourself and other people by turning up late. You get the best out of the rehearsal by being settled for the start, and being there for the whole thing. If there's a conductor, they're happiest when everyone turns up on time, and a happy conductor is definitely better than an unhappy one!

0 Comments

One of the best analogies I've ever read for how music lessons should be is in 'The Perfect Wrong Note' by William Westney - which compares the process to the student working on trying to get a machine working. They've tried all sorts and had some success, but when it comes to their lesson, they bundle up all the loose bits and bring them along to show their teacher - "I've managed to get this part fitted in here and working, but I can't figure out how these go together or how to make them turn round". Lessons are the place to get help with the things that you can't do or aren't sure about. I'm also always happy for students to text or email me between lessons if they have any questions - it might be something that's easily fixed with a quick answer or I can give you some ideas to try out in your practice. You can text me a picture of something in your music, asking "what's this again?!" or if you're really struggling to find a recording, I might have something I can bring along to your next lesson, or I might be able to record a quick mp3 of a few bars to help you out.

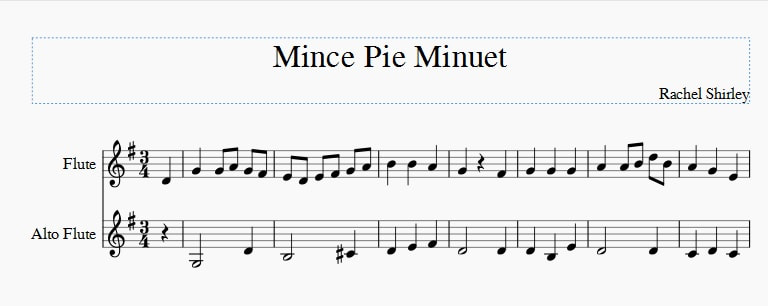

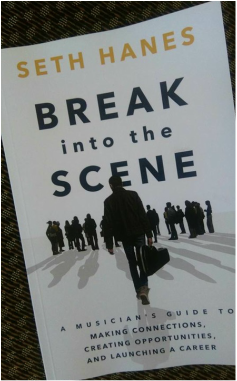

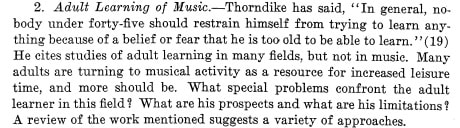

But music teachers can't be available 24/7 and there are other things you can do between lessons to help you figure out the bits you're not sure about. I still have occasional lessons, but part of learning music is also 'learning how to learn' and finding out where to go if you're puzzling over a problem. When you're used to looking these things up on a regular basis, it becomes habit, but if you're not and you're in the middle of a practice session thinking "help! I have no idea what to do!" then it can be difficult to know where to start. So I thought it would be useful to put together a page of resources in one place, to help students if they're stuck with something between lessons. There's a bit of a flute focus, but most of it will be handy for players of any instrument. (Side note: a lot of these are online resources, and a few people have mentioned to me that they get distracted if they have their phone/ computer nearby whilst practising. If that's the case, then maybe 'allow' yourself to have your phone/ computer/ technology item of choice only for the first or last, say, ten minutes of your practice session, when you're dealing with the specific issue that you need to look up. You might want to stop notifications from popping up for that time, if they're likely to lead you astray. Then you can either put it away for the rest of your practice session, or if you use it at the end you can finish, pack up your instrument and go and check all your social media if that's what you want to do!). How does this piece go again? As much as the sheet music tells us 'how a piece goes', there are times where we all get stuck with how something is supposed to sound. Some books come with CDs or downloads of the tracks which can help with this, but if they don't then YouTube is usually my first stop. As with any online resource, you need to exercise some care - professional performances are more likely to be accurate, but that's not to say there aren't lots of brilliant home recordings out there too. But do be aware that what you hear might not be exactly what's on the page, whether that's through error or intentional interpretations of the piece. Other online music resources like Apple Music and Spotify are great too, and it can be helpful to listen to different versions of the same piece to get ideas about how to play it. If you can't find the exact piece, then even looking up something in the same style can give you ideas about how to play it, for example looking up Minuets or Waltzes to give you a feel for those sort of pieces. How do I do that? YouTube also has some great instructional videos. If you're struggling with how to do something in particular on your instrument, it's worth a search to see if anyone's put up a video about it. Now, you will possibly find varying and even completely conflicting views on aspects of technique, but I always encourage students to experiment - so try a few out and see what gives you the results you're looking for, remembering that there is no such thing as "one size fits all" when it comes to playing an instrument. You'll also find lots of web sites written by flute players and teachers, with advice about technique and about particular pieces. Jennifer Cluff's site has a wealth of ideas and answers to questions sent in by players. Paul Edmund-Davies' Simply Flute has some great exercises accompanied by videos showing how to work on them. If you're exploring how to play alto or bass flute, have a look at these blog posts by Carla Rees on different aspects of the low flutes. If you're looking at some of the different techniques on the flute besides 'normal' notes, I think the short video tutorials at Flute Colors are brilliant - whether you've come across one of these 'extended techniques' in a piece, or you just want to try out making a different sound! You can also try asking on online forums or Facebook groups - there are plenty out there for general music and for specific instruments, which also have the benefit of acting as a community where you can chat to and compare notes with other people learning. Again, you'll probably get differing views on the same issue, so it pays to be open-minded to trying different possible solutions. I love arriving at a lesson to a student telling me they've been reading different ideas about how to do something - we can then play around with these in their lesson and see what works! How do I play that note? If you're stuck on how to play a particular note, fingering charts are what you need. You can often find these in the back/ middle of tutor books, or more detailed books (including alternative fingerings and trills) are available. You can also buy fingering charts that are small enough to carry around in your bag or flute case. If you prefer to go online, I like the charts at WFG and FingerCharts (which also has a really handy app for Apple and Android). What does that word mean? What is that squiggly sign on the music? If you're not sure or can't remember what an instruction on your sheet music means, whether it's a foreign musical term or a sign for an ornament, there are a few places you can look these up. If it's a word, just Googling can work (although it's often worth adding 'music' to your search term as the usage in music might be slightly different to the everyday translation). Likewise if you look up 'musical ornaments' you'll find lots of pages explaining what the symbols mean, such as the BBC GCSE Music resources. For generally improving your music theory knowledge, MyMusicTheory is a brilliant site with clear explanations and exercises to work through. If you prefer to have a reference book to hand, the classic is the ABRSM 'Pink Book' (and it's second volume, the blue one). Still stuck? Ask! Ask your teacher, ask a friend who plays an instrument, ask the other people in your band or orchestra. Lessons are just part of the picture of learning music, and you can learn as much from other people (which is one of the reasons why playing in a group is so good for your progress, as well as being enjoyable and social!). People learn in different ways, with different methods and pick up skills in different orders, so they might know something you haven't learnt yet, or have tried a different technique for whatever it is you're trying to do. And the same applies to you too - you might be able to answer someone else's question or suggest a solution to something that's been puzzling them. Or maybe you'll be able to work it out between you! Do you have any resources that you turn to when you're stuck? More suggestions are always welcome!  Sometimes musicians are guilty of not thinking much about composers. We open a book and there's some music printed there, and we play how we think it goes. We might puzzle over the composer's 'intentions' and debate whether it's important to play exactly what they 'meant', and how we can possibly know that if the composer lived 300 years ago. I have never considered myself a composer. I've written short compositions as answers to theory exam questions. I wrote a flute and piano piece for a competition run by Flutewise magazine many years ago (it got some nice feedback on the melody but I forgot to leave the flute player enough room to breathe!). I wrote some bits and pieces for composition classes at Uni, and my setting of the words to 'Down in Yon Forest' was performed by the University choir at the Christmas service one year. I started work on an LCM composition diploma a few years back, arranging a piano piece for a wind trio. I've arranged a few of the local Sheffield carols for our flute choir. I'm still not a composer though. There's a risk of a bit of a 'them and us' feeling between musicians and composers. We could see the people who write the music as some sort of anonymous authority figures, imagining them to create these perfect finished pieces out of nowhere. Rather like the idea that 'good' musicians can just perform a piece first time, it's quite off-putting if you think about composing and imagine that you can only do it if masterpieces pour instantly from your pen (or computer software). Both things are a process and involve hard work! I've been lucky enough to work closely with some composers over the last couple of years. At Sheffield Flute Choir, we've worked with local composers Tim Knight and Jenny Jackson as they produced new works for flutes. Jenny ran a workshop on composition for flute this year, where I got to work with budding composers as they learned about the composing process and produced a piece for solo flute in just one day - this was an amazing experience to work with people writing music from the very start, to talk about how they got what they wanted it to sound like onto the page, and how I as a player interpreted what was written down. I've played brand new works by all of the Platform Four composers, seeing pieces evolve as rehearsals progress. I've met the lovely Keri from Masquerade Music, and the equally lovely Rob and Lynne from Forton Music, who are all running small businesses writing, arranging and publishing music for woodwind. I've performed pieces by David Barton - you can find us playing his 'Imagination' on YouTube here. I've also recently been reviewing new sheet music for Pan, the British Flute Society magazine, from publishers big and small - and it's struck me that it's a great privilege to be trying out this music that composers have sent out into the world, hoping that we like it. While we might worry about 'getting the composer's music right', they worry about whether it's playable, enjoyable, too hard, too easy, ready to be heard. Social media also brings us closer to composers, hearing about the process of writing music (and all the other things going in their lives at the same time too!) - it's through social media that I've discovered the exciting new flute music of Nicole Chamberlain and the utterly joyous 'An Harmonic Disquisition Upon Various Types of Cheese' for piccolo quartet by Brandon Nelson. I've recently read Brandon's new book 'Writing and Living in the Real World: Advice for Young Composers'. This is an excellent guide for anyone who wants to write music as a career (or part of a career). It isn't about how to compose - other than some good ideas about time management and motivation - but covers the practical side of getting your music out there: publishing and marketing. There's also some very thoughtful chapters on originality, creativity and artistic identity which are worth reading by anyone who has or wants to have a creative career. And far from the idea of the composer up in their ivory tower magically creating masterpieces, it emphasises the importance of sitting down and putting the work in: "Keep writing. Even on days you "just don't feel it"." So, back to being a composer (or not). I haven't found myself struck by inspiration out of nowhere. However, I have found myself in need of more duets to use with my students - ensemble playing is so important (and fun!) and I'm endlessly trying to find enough pieces to fill the gap between easy and difficult duets. Many of the composers/ publishers above have some great books, but I always want more. I've also had a few conversations this year about the fact that more of us than ever have 'big' flutes (alto, in particular, and bass) and we always need more things to play on those. I want music that will work if I take my alto along to a lesson - both for me to play and to introduce students to it when they're ready. So, I decided to try and write a few duets to fill those gaps. I'd been doing a lot of work with students on discovering the Baroque dance forms that appear in so many flute pieces, so those seemed like a good place to start - writing my own simple versions of those. I used the key signatures and rhythms that students are familiar with from around Grade 3 standard. I deliberately didn't add any dynamics or articulation so they could practise working out their own in preparation for real Baroque music. And because I like to tie music theory in to what we're working on, the harmonies are mostly nice and straightforward so that students at that level can analyse it and figure out the chords and cadences. So this is very much composing with a particular (educational) purpose in mind, but they're hopefully enjoyable tunes too! If anyone else thinks they would find them useful for teaching or just playing, I've uploaded a few for sale at Sheet Music Plus, including a silly seasonal one... and yes, there is a bit of a theme to the titles! To the real composers I know, have met, have worked with, follow on Twitter, or just encounter your music - thank you for your hard work, persistence and bravery in sharing your work with the world - we might grumble about you sometimes ("you want me to play WHAT?!") but where would we be without you? The other day, I came across this article from 1938 entitled 'Needed Research in Music Education'. Leaving aside the "nobody under forty-five" bit (lets just make that "nobody"!), it's another to add to my collection of quotes which basically say "someone should be researching adult learning in music". They pop up in the literature every few years, whilst actual research into adult learning appears at a slow trickle. They're one of the things that keep me going with my research, when the thought of the long, slow process seems overwhelming.

Articles about adults learning music appear in the more mainstream press now and then too - why it's good for our (ageing) brains, the story of someone deciding to take up the piano after dreaming of playing for years. I was pleased to spot a magazine article this week about the benefits of learning music as an adult, but then rapidly disappointed by lines about "demoralising (or just plain boring) school lessons" and "shake off the shackles of childhood piano lessons and start having fun". There's nothing necessarily wrong with teaching yourself or making use of YouTube videos, as the article suggests, but this disparaging view of music teaching got my back up. Yes, there are boring/ miserable lessons/ teachers, but there are so many teachers that I know who are trying their best to make learning music enjoyable and engaging for all ages. Although the article pushes the social benefits of music, it takes confidence to go and join a group - I'm not sure how easy some people will find it to step out from behind their computer and go out to play in public. That can be something that a teacher can help to 'hold your hand' through, playing with you in lessons, arranging informal opportunities for you to play with and in front of other people, suggesting suitable ensembles to try out. Going along to lessons is a social interaction in itself, and don't we spend enough time in front of a screen as it is?! I have a couple of other issues with dependence on video lessons - firstly, there isn't someone there observing you and helping you out. I've come across adult learners who've struggled with teaching themselves through online courses, because they're trying to follow a set of 'one size fits all' instructions. The instrument hasn't been set up properly for their particular body shape and size, their hand position is all wrong for the length of their fingers, and they're wondering why it doesn't sound right, and even more worryingly, it feels uncomfortable. Look at just a few clips of professional flute players and you'll see variations in how they use their hands, arms, mouths - because bodies aren't all made the same! This is something that a teacher can help to work out, helping you to avoid injuring yourself at the same time (it might seem difficult to injure yourself with an instrument but the damage that musicians do to their bodies is a big issue - if you're doing a repetitive movement many times, you want to be doing it in the best way possible). They're also there to help with the mental and emotional aspects of learning - supporting you through the frustrating times and helping you navigate the process of learning music alongside all the other challenges in life. I entirely understand that it costs more to take lessons than to watch YouTube for nothing (and clearly I have a vested interest in people taking lessons!), but I wonder whether sometimes 'free' isn't the bargain it seems to be. My other issue is an apparent obsession with speed (of learning, not of playing!) - online teaching resources I've seen use phrases like "fast-track your results". One, specifically for adults, promises to "skip the simplistic and slow approaches used with children and will get you playing in no time". While I'm not doubting - and research, including my own, suggests - that adults need some different approaches to children, I am wondering what's so wrong with 'simplistic and slow'? I certainly see a desire for quick results in many students (as much in children as adults, I would say), but surely there is nothing wrong with taking your time? As well as getting away from the screen, why can't learning music also be a change in pace from the rest of life? I'm reminded of the 'slow food' movement which celebrates traditional methods of growing and cooking, and of the trend for mindfulness which encourages people to slow down and observe. Why should learning music be a race? Why shouldn't we enjoy the gradual process, and celebrate the beauty of playing something simple well. Perhaps adults do want quick results. Maybe they don't want teachers (although my research suggest that that plenty of them do, and that the teacher-student relationship is really important). I suspect that what really works well for most learners, whatever their age, is a combination of approaches - individual lessons, playing with groups, making use of some online resources, experimenting on their own. We need to look at what benefits learners most - musically, but also mentally and physically - is it the quick fix that seems initially most appealing, or is it taking your time and immersing yourself in the long, wonderful process of learning? We could say that 'slow and steady wins the race' but I think what's most important is that it isn't a race! 'Getting everything done' is a common issue in my life - trying to balance playing, teaching, all the admin that goes with those, doing research, all the usual things that you have to get done in life and actually 'having a life' isn't always easy. I see it in my students too. It's proving to be a frequent theme in my research (and anecdotally) with adult learners - how do you find time to practise an instrument, learn music theory, read about the history of your pieces etc, whilst also doing a full-time job, bringing up children, and going to the gym regularly (or whatever it is that fills your weeks)? I increasingly see it with younger students too - how do you fit in learning music, all that homework, competing with your sports team and all those birthday parties, and still have some time to hang out and do nothing as well? When you're younger, you probably don't think in terms of 'productivity'. As an adult these days, the word is everywhere. We're meant to be getting loads done (whilst simultaneously taking plenty of time out for self-care). There's a massive industry around teaching people ways of doing more in less time, books packed full of methods to help you be more productive - if only we could find time to read them all! I was pleased to be chosen as part of the pre-launch reading group for Prof Mark Reed's new book The Productive Researcher - it's great to be supporting someone who's self-publishing their work, and I was hoping to find ways to make the most of my time. I wasn't sure at all what to expect, and worried slightly that it would be full of what felt like unachievable methods for 'doing more', just tailored towards academics. What I actually got was not at all your usual ‘how to do more’ book. Mark writes in an open, friendly way, sharing his own experiences of discovering how to be productive, but also happy in your work. There’s clear academic research behind it – in looking at other people’s theories and approaches to productivity – but it reads like the words of a supportive, gently challenging mentor. You can read this book quickly and pick up useful ideas from it, but I think to get the best from it you need to spend some time and mental energy to work through the questions and exercises, and commit to trying to use the principles. It’s not (nor does it promise to be) a quick fix, but it really gets to grips with what lies behind our struggles with ‘being productive’. The first part of the book proposes that to be productive in our work, we need to know why we’re doing the work, and asks us to pin down our motivations – I particularly liked the idea of having back-up motivations for the times when our main ones falter. There’s a re-framing of SMART goals as “Stretching, Motivational, Authentic, Regardful and Tailored” which I felt was much more motivating than the original concept. The second part describes ways of putting these motivations and goals into action. There’s a focus on prioritising and using your time well – that the way to feel/ be more productive is to spend less time on the things that don’t contribute to your overall goals. I loved the idea of firing up your day with enjoyable work first, rather than saving the bits you like as a reward for getting through the less fun stuff. There are practical tips on managing the time you spend in meetings, on social media, and dealing with the never-ending stream of emails! I can imagine that some of these would take a fair amount of willpower to implement in the pressured atmosphere that academics are working under, and there are bigger issues at play around what is expected of researchers, but some of these steps would definitely help gain back some sense of control to your working life. Although it's aimed at researchers, meaning that some of the scenarios are academia-specific, e.g. submitting papers to journals, examining a PhD thesis, there's a lot in this book for anyone who wants to feel like they're making the most of their days. Being really clear about your motivations and priorities, and learning not just how to say 'no' but how to decide what to say 'no' to, are lessons that anyone could find useful. Yes, there are days when whatever procrastination activity you like to indulge in seem far more appealing than practising your scales or going for a run in the rain, but if you're clear about your overall motivation and what's important to you (you want to be able to join a band and sight-read new pieces at rehearsals, or you want to complete a half-marathon) you can keep revisiting that to keep you going and enjoying what you do. Bloggy disclaimer things: I received a free copy of the ebook version of The Productive Researcher and was asked to write an honest Amazon review (which I did - it's basically a reduced version of this blog post). The links above are my Amazon affiliate links which mean that if you buy the book through those I will receive a small amount of commission.

I've been a member of the Incorporated Society of Musicians (ISM) since I started teaching. Essentially there's a choice of two 'unions' for musicians, the ISM and the Musicians' Union, both offering support, advice, legal protection, training, online communities and real-life meet-ups. I've benefited from the ISM's resources for teachers - I use a version of their teaching contract - and I couldn't (legally) do my job without their Public Liability Insurance (although I've thankfully never had to claim on it!). They run regular webinars which have given me some interesting food for thought on topics such as 'teaching in the digital age' (how do we keep the attention of children who are used to social media and computer games?), career planning and psychological wellbeing for musicians.

Their blog is a great resource of ideas and opinions from different musicians, too, and I've particularly enjoyed the new Teacher Focus series, where a private teacher writes about their own job, thoughts and experiences. So I was very happy to answer a call for more contributions to this series, and reflect on my background, principles of teaching and hopes for the future - you can read my post at https://www.ism.org/blog/private-teacher-focus-rachel-shirley. It's a well-known fact that music teachers have the ability to tell exactly how much practice you've done between your last lesson and the current one. You can't fool us. You don't need to make the guilty admissions that you "haven't done much practice" because we already know. Even on those days when you know you've done loads of practice and it feels like it's not showing when you play in front of your teacher, we can tell.

Well, OK, we can't tell precisely how many minutes of practice you've done, but generally, teachers can tell if there's been some work since last week. We can tell because we have done and still do go through the process of practising ourselves. We're familiar with the satisfaction that comes when that structured, gradual work pays off, and the frustration that you feel when you know you've put the work in but the desired result hasn't materialised yet. At this time of year lots of people have been making resolutions to practise more, take up a new instrument or return to a neglected one. And we seem to be bombarded with quotes intended to inspire and motivate us. The two above have popped up in my view just this week. Some words can be helpful in spurring us on, but I'm not sure about these ones. Both of these give the impression that what we're aiming for in music is 'perfection'. That you can never be a professional unless you can do things without any mistakes. Yes, it's a good thing to aim to keep improving your playing, and if you want to perform a piece, you want it to feel as secure as possible, but these quotes suggest that you're not 'good enough' if you're not perfect, and that can be quite demotivating. I think this sort of pressure can lead to unhealthy stress - feeling like you can never 'get anywhere' with music if you're still making mistakes. Of course professionals still get it wrong! And how would you even begin to agree on a definition of perfection? A more useful piece of advice I read recently appeared in this blog post by The Self-Inspired Flutist: "realise that practising is the point". In other words, as a musician, you're going to spend more time practising than any other activity, so if you can learn to love it, that will go a long way to enjoying making music. That doesn't mean that it will always be fun and sound lovely - the point of practising is to deal with the bits you find difficult, to make the mistakes and find out how to fix them. It can be frustrating and downright annoying at times, no matter how many years you've been doing it for. But if you can find satisfaction in that process, I think that can make a big difference. I'm playing in a concert at the beginning of February, and I reckon on the day I'll be actually physically playing the flute for about fifteen minutes. I haven't kept track of how long I've practised the pieces for (especially as I've played a couple of them before, so the initial practice was a while ago and I'm now revisiting them), but I can tell you that it has definitely been hours. Then there's the general ongoing practice of improving tone, technique, breath control etc which will contribute to playing these pieces. Seeing the outcome of all these things in a performance is of course fulfilling, but getting absorbed in the process is also a wonderful thing. Finding out what your mind and body can do can be quite amazing - from the beginner who starts to train those tiny muscles around their lips to make a sound on the flute, to the advanced player who discovers a small tweak to their hand position which improves their technique. Things you do other than actually playing your instrument can help your music-making too. Lots of musicians turn to meditation to help with nerves and concentration, and to exercise for fitness and stress-relief. I've recently re-started going to the gym, and the fact that I know it helps my playing is always a big motivation. Some achy muscles led me to reading about recovering from workouts, and everything I saw emphasised the importance of rest. One article I read said that fitness doesn't happen in the gym, it happens in the times between, when your muscles are recovering and rebuilding - and practising an instrument needs those times in-between too. You are using both muscles and mental energy, and those need to be rested. So this is why I won't tell you to practise every day, but most days, and to do enough but don't overdo it. Take rests, have a cup of tea, have a day off, go and listen to your pieces rather than playing them, go and listen to something completely different, lie on the grass and stare at the sky for a bit (though maybe not at this time of year). Of course you won't always do all of this, and sometimes you'll give yourself a hard time for not being perfect, for playing the wrong notes, or for not practising enough or for doing too much (and sometimes I need to be reminded to follow my own advice). And that's OK. It's difficult to sum that up in a snappy quote though.  I signed up to Seth Hanes' email list a while ago, after coming across 'The Musician's Guide to Hustling' through a Facebook group. Seth is a musician and a marketing consultant, having realised before graduation that he needed to know about marketing and entrepreneurship and throwing himself whole-heartedly into getting to know all about it. He now advises artistic clients and businesses such as the Pennsylvania Philharmonic and The Conservatory of Musical Arts. I was impressed by how he'd combined his musical and marketing knowledge. So when an email came through from Seth asking for beta-readers for his new book 'Break Into the Scene', I jumped at the chance to combine my own skills - a musical background and editing/proofreading - and offer my help (plus, I have to admit I was really curious about the book, and this meant I got to read it early!). When the book came out a couple of months later, I ordered a copy - in fact, it was the first thing I used my new student status to get a discount on! I read it (again) on the train back from a day at Uni - it's about 160 pages, so a quick read if you want to sit down to it in one go, but also written in easily-digestible sections, so you could grab it for ten minutes at a time and still get plenty out of it. The book is part myth-busting and part practical advice. Essentially - yes, you need to practise your instrument to get good at it, but that alone will not get you work - the gigs will not 'magically' come to you. Certainly when I was training, the myth of 'discovery' was quite powerful. If you worked hard and got really good, someone would come and find you and propel you to stardom. Maybe that happens on very rare occasions, but the vast majority musicians need to put some effort in to 'getting themselves out there'. Seth uses his marketing knowledge to set out steps that you can take to get in touch with people and make opportunities for work as a musician. Yes, he uses the word 'networking'. This is a word that always makes me cringe a bit. But I like Seth's take on it - he quotes his friend and mentor Charlie Hoehn: "The best networkers don't call it networking.... they call it being friends" and says that "actively trying to network with people almost always comes across as fake... it should always start from a place of creating authentic relationships". This rang huge bells for me - having friends who share your experiences in different areas of your life is utterly invaluable (in my case, musicians, academics, people who are self-employed in different fields - although of course I have friends who aren't any of those things and I don't value them any less!). And the best, most enjoyable work, I find, is with people who you really get on with. But of course you need to make contact with people in the first place. Seth's take on this is a bit different from the usual advice. The biggest surprise for me in this book was the advice not to bother with a website. Since I'm writing this on my website, and my website is where a lot of my work comes from, my immediate reaction was to reject this... but actually, he's not saying never to bother with a website, just that it (along with professional photos, social media, etc) isn't vital to start with. Instead, Seth offers an email template for getting in touch with people and offering whatever it is you have to offer. And while you might want to tweak the wording to suit your own style, the basic premise of 'putting yourself out there' and the guidance for taking the first steps is what I think really makes this book. It's like a reassuring voice saying, it's OK, you can do this, I know it's scary, but I've done it, other people have done it too, and here are the good things that can happen. Some of the 'good things' described really made me smile - as well as being success stories, they sounded like a lot of fun! There's some excellent practical advice on what to do when you get work too - the 'Skills That Have Nothing to Do With Talent' chapter contains some 'rules' which are aimed at freelancers, but can apply to most musical situations - in fact, a lot of other situations in life too. These fall broadly into practical skills (timekeeping, replying to messages, being prepared) and social skills (be friendly, offer help, "don't be a whiner"). All common sense really, but well worth a reminder. It can be easy when reading books like this to come up with reasons (excuses) why you can't do these things, why your situation is different, why that wouldn't work for you. Seth is in the US, so some of the systems and organisations he described don't exist in the same way elsewhere (I'll admit to still not quite understanding how the US high school band system works), but it doesn't take too much of a leap of the imagination to think of alternatives in your own area. And of course, not every bit of someone else's advice is going to be right for you. I still felt some resistance to the 'marketing' language (I can't imagine myself sending an email saying "I wanted to reach out" but again that's probably a bit of cultural difference, and the need to adapt things to suit you!). But if you need a quick dose of motivation, along with lots of straight-talking advice and some virtual hand-holding, I think this book strikes the right balance. Last night BBC Four showed the first episode of All Together Now: The Great Orchestra Challenge. Like Bake Off for musicians, this is a series where we follow several amateur orchestras through various rounds until a winner is decided (and gets to play at Proms in the Park). I wrote of my reservations about the idea when it was first announced, so it was with some hesitancy that I switched on last night.

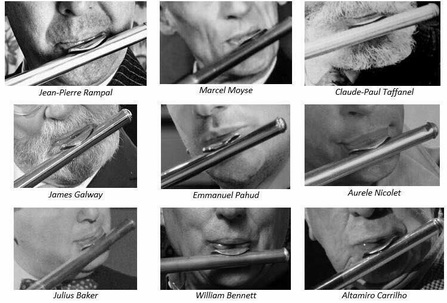

I have to say I enjoyed most of the programme - it was lovely to hear the stories of the orchestras and some of the individuals who played and conducted them. It was particularly great to hear about how being part of the groups had enhanced people's lives, made them feel part of a community. It was fascinating to see how they worked in rehearsals, and responded to the professional coaching and intensive mentoring sessions, to hear them talk about practice (or lack of!) and the challenges of playing at a certain age, or when you've got long working hours and family to consider. Seeing/ hearing the different styles and characters of each group was really interesting, as was seeing/ hearing the progress they made over a month with the pieces they'd been challenged to learn. The competition element was kept fairly low-key, until right at the end, when each group performed their piece and there was the typical "we have to say goodbye to someone" line-up. I agree with this review from theartsdesk.com that this felt tacked-on, 'tacky and unnecessary'. Could we not have just followed the progress of all these amazing people across a few months? Could they not have all played in a concert at the end, celebrating amateur music-making and their achievements? Maybe that wouldn't have provoked as much interest as a competition. Classical music has been in the news for other reasons connected to competitions too. After the Olympics, there were questions around why there is so much more funding for sport than there is for the arts. Why 'elite' sport is seen as a good thing but 'elitism' in music isn't. That particular question grabbed my interest as a linguist - my initial thoughts are that it is in part down to the different usage of the terms. You just don't really hear anyone talking about 'elite' musicians in the same way as they do about elite athletes, even though the process of training is not actually that different or any less intense. Where the term is used, it's negative, around classical music being 'elitist' or for 'the elite' (although I have also seen some discussion about certain sports suffering from 'elitism' - debates around lack of access to particular sports to people coming from state schools, for example, which could also apply to music education in some areas). I think this is something that could make a good corpus linguistics study, to get some data around the usage of the words - maybe I'll set aside some time for a mini research project! I do wonder, though, if there is any connection between these views (and funding levels) and the fact that sport is generally competitive and music is generally not - not in quite such an obvious way, anyway. Music competitions exist, but the usual way for people to experience music is a performance/ concert, whereas the normal way of experiencing sport is to watch a competitive match or race. Do people just like the structure of competition, the tribalism of supporting a team? Is musical performance 'elitist' in a way that sporting competition (whilst involving an 'elite') is not? This photo has been doing the rounds on the flutey internet recently (I don't know where it originates from, so apologies for the lack of credit). These are some of the best flautists of the last couple of hundred years, and in particular these are their embouchures - the shape they make/ made with their mouths when playing. If you'd like to look at lots of other embouchures, there's a web page full of them over here: http://www.larrykrantz.com/embpic.htm. The point is that there are all sorts of differences between them - how much lip is above/ below the flute, what angle the lips/ flute are at, all sorts... and of course their lips are naturally very different in the first place. I saw one of the above flute players at the weekend - at the British Flute Society 'Flutastique' Festival, which was celebrating the links between British and French flute playing, and William Bennett's 80th birthday. Looking around the event was a perfect demonstration of the idea that one size doesn't fit all! Watching the performers' recitals - all wonderful players with fantastic, but different, tones - you could see different embouchures, different ways of holding the flute and using the fingers, different ways and degrees of movement when they played. And then there were the hundreds of attendees - on the Friday morning we had a great warm-up session with Katherine Bryan, and although we were all aiming at the same thing, 'good' relaxed posture and playing a nice clear 'B', a glance across the room showed numerous permutations and combinations of posture, hand positioning and embouchure. The same variations were in evidence at the manufacturers' stalls where people were trying out different flutes and finding that some worked for them and some didn't. When you watch someone playing the instrument you play, it's natural to analyse what they're doing (especially if you admire their sound or technique). If they sound that good, they must be doing it right! But seeing so many players in close proximity made it really obvious that there is no one 'right'. Trying out things that other people do is a great idea, but we have to work out if they work for us or not. We probably have to borrow bits and pieces from different people, rather than copying any one person's complete technique (unless they're your identical twin, in which case, it might work). It was fascinating to watch players on stage with some of their own students, and see the things that were similar but also those that were different. Through all this, it's worth considering that even if someone is really, really good, they might still be doing things that aren't ideal, even for themselves! They might have habits that they'd like to break out of but haven't quite managed to yet. They might have to work round issues such as fingers that don't quite do what they'd ideally do. I find hands fascinating - they vary so much, and trying to get a good playing position on the flute is a case of careful work between the student and teacher to find something that works for them (and then may need to be adjusted as they grow - a few of mine seem to have had finger growth spurts recently!). And what about attending a flute festival? That's not something that's going to suit everyone - it's pretty intense listening to, talking about, trying out, playing, thinking about flutes for a few days. If you're the sort of person who likes throwing themselves whole-heartedly into a subject for a weekend, then definitely worth it (it's not cheap, so whilst it's not a bad idea to miss the odd session to clear your head, you want to make the most of it). Not something I'd want to do every weekend, but every couple of years - definitely! The little badges below were my souvenir of the weekend - what a lovely varied bunch they are too! |

Keep in touch

I have an email newsletter where I share my latest blog posts, news from the flute and wider musical world, my current projects, and things I've found that I think are interesting and useful and would love to share with you. Expect lots about music and education, plus the occasional dip into research, language, freelance life, gardening and other nice things. Sign up below! Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed